The Game of Football Was a Lot Different for Early Massillon Teams

If there’s one sport that draws Americans closer together more than any other it’s the game of football. It attracts the largest crowds, receives the greatest media attention and is played at all levels, from the many youth organizations, through over 14,000 high schools and several hundred colleges, and culminating with the professional organizations. During the season the teams may play games just once a week, but in between football is the talk of the sports world each and every day.

Football has been around for over a hundred years, the first game having been played between two college teams, Rutgers and Princeton, in 1869. High schools picked up the sport in the 1880s and then the game added play-for-play by professional athletes in the late 1890s.

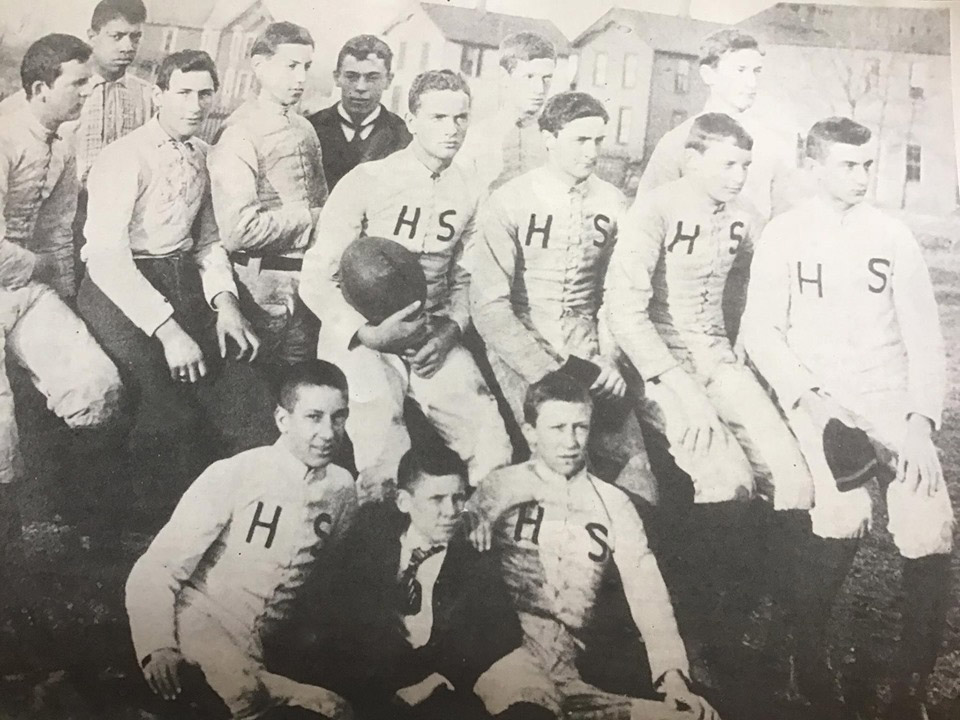

Massillon got its start in 1891 and has now been fielding teams for 127 years. But the game those early Tigers played is quite dissimilar to the one we see today. Different scoring rules, drop kicks, off sides and many other nuances were all in vogue at that time and some were subject to different interpretations by the referees as opposed to now.

In addition, many locals were unfamiliar with the new sport, although interested in either watching or participating. So, in order to educate those new to the game, the Massillon Daily Independent in January of 1890 made a stab at publicly explaining the complex rules. Below is that article. Some of it is confusing, so I hope you can understand the rules better than this writer does.

EXHILARATING SPORT

THE GAME OF FOOT-BALL, AND HOW IT IS PLAYED

Diagram and Dimensions of the Ground – The Players’ Positions and Other Interesting Points About the Great Collegiate Sport

Foot-ball as now played by the American colleges is a game that arouses the enthusiasm of the spectator to a higher pitch of excitement than any other sport, and there is no game where the requirements of the participants are greater or more diversified. The elements so essential to the success of the runner or tennis player are far different from those demanded by the oarsman or wrestler; but the foot-ball player needs them all, and in no athletic contest can the display of pluck, strength, endurance, agility, and quick judgment been seen to better advantage.

The best player is not necessarily he who makes the longest runs or kicks, says the Chicago Inter Ocean, but the one combining good, hard individual play with team work, and is always willing to let the man make the brilliant play whose chances are the best. The training to thoroughly fit one’s self for a match game is as arduous as it is for a boat race; in addition to the daily practice, a run of two to three miles is necessary for the wind; smoking, drinking, pastry, and rich food must be given up, and plenty of sleep taken. Five minutes of brisk work will cause the player who enters a game in poor condition to make many good resolves for the future.

The best player is not necessarily he who makes the longest runs or kicks, says the Chicago Inter Ocean, but the one combining good, hard individual play with team work, and is always willing to let the man make the brilliant play whose chances are the best. The training to thoroughly fit one’s self for a match game is as arduous as it is for a boat race; in addition to the daily practice, a run of two to three miles is necessary for the wind; smoking, drinking, pastry, and rich food must be given up, and plenty of sleep taken. Five minutes of brisk work will cause the player who enters a game in poor condition to make many good resolves for the future.

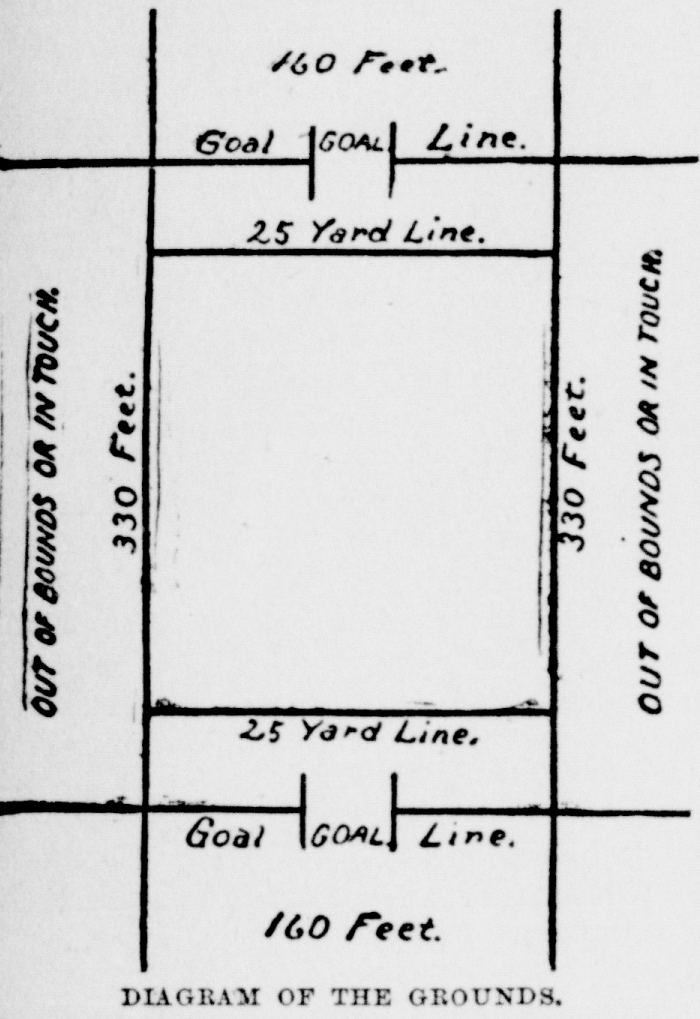

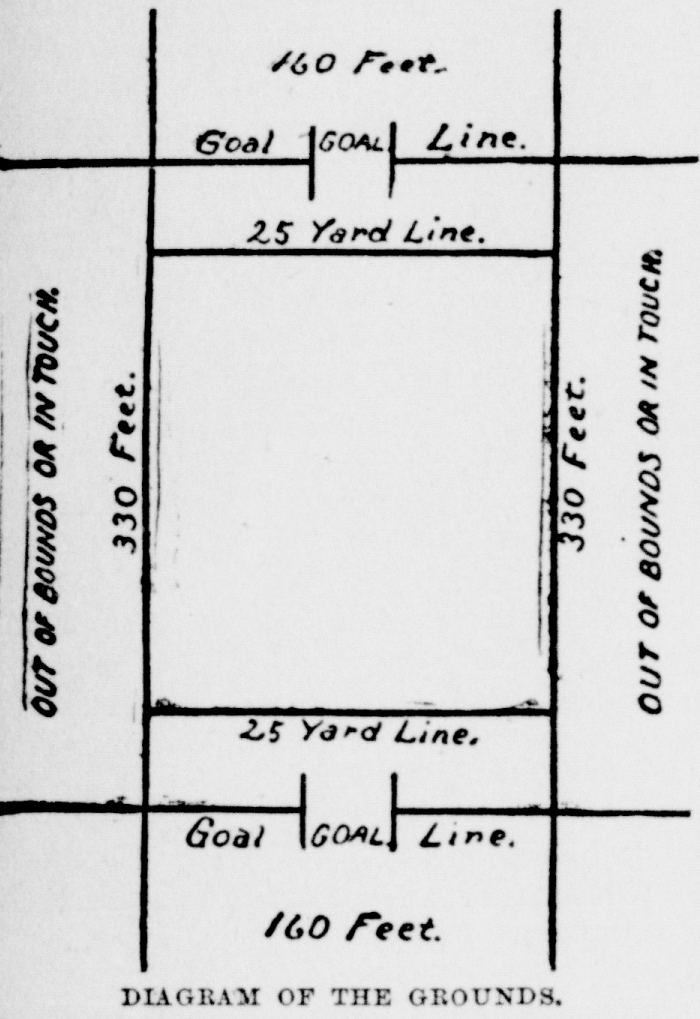

The grounds must be 330 feet in length and 160 feet in width, with a goal placed in the middle of each goal line, composed of two upright posts exceeding 20 feet in height, and placed 18 feet 6 inches apart, with a cross-bar ten feet from the ground. The following diagram will illustrate:

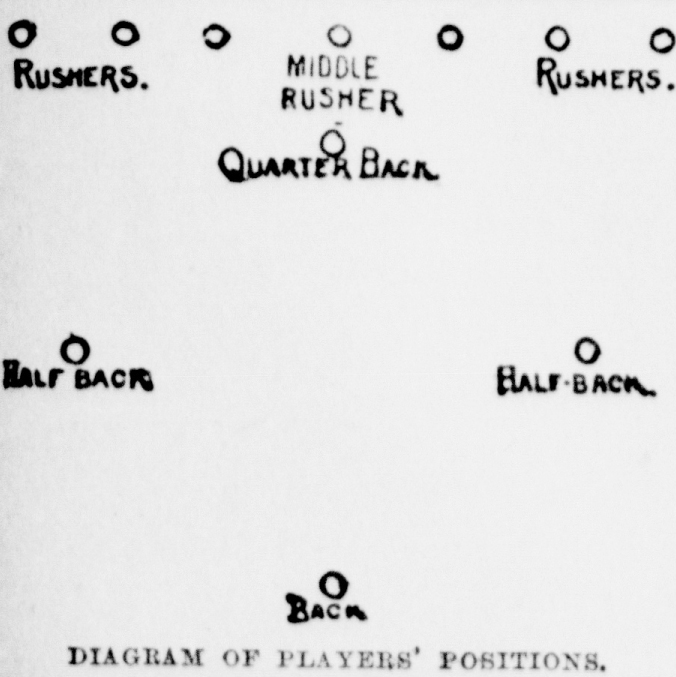

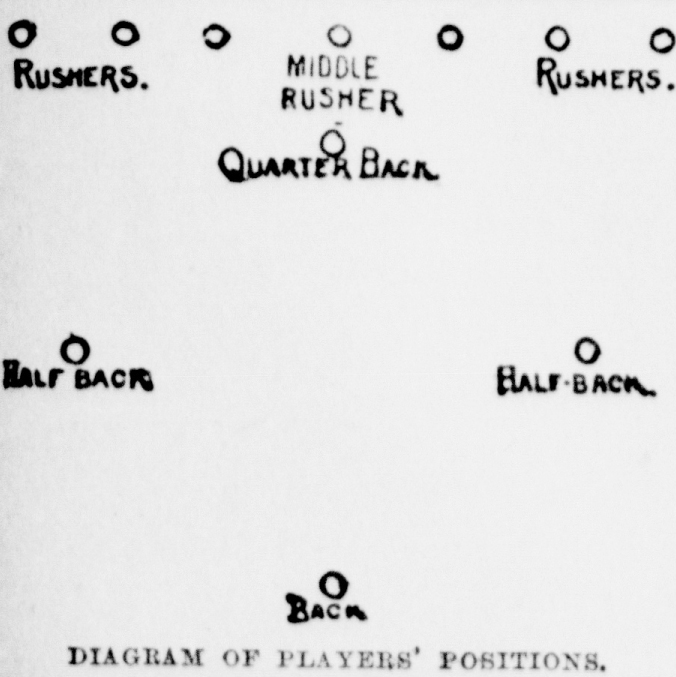

There are eleven men on a side, generally seven in the rush line, a quarterback, two half-backs, and a back. The prime qualifications of the rushers should be weight, strength, and endurance, for on them devolve the duty of forging ahead by running with the ball. They need know little or nothing about kicking, and should never touch foot to the ball except in case of a free kick. Even then it is not necessary, for a place kick can be taken instead by one of the other players, and is generally preferable. Weight is not so essential for the rest of the team, but in addition to the other qualifications of the rushes they must be good kickers; also they should be sure tacklers to stop an opponent if he succeeds in breaking through the rush line. The following diagram shows the relative position of the players:

There are eleven men on a side, generally seven in the rush line, a quarterback, two half-backs, and a back. The prime qualifications of the rushers should be weight, strength, and endurance, for on them devolve the duty of forging ahead by running with the ball. They need know little or nothing about kicking, and should never touch foot to the ball except in case of a free kick. Even then it is not necessary, for a place kick can be taken instead by one of the other players, and is generally preferable. Weight is not so essential for the rest of the team, but in addition to the other qualifications of the rushes they must be good kickers; also they should be sure tacklers to stop an opponent if he succeeds in breaking through the rush line. The following diagram shows the relative position of the players:

The game is commenced by placing the ball in the center of the field, and, if there be no wind, the side winning the toss choosing as a general thing to kick off. But if the wind be blowing, however slightly, the winner will of course play with the wind, for this is a most important factor in foot-ball, a stiff breeze deciding whether the game shall be a kicking or running one. We will suppose the ball has been kicked off and stopped by one of the opposing half-backs, this player tackled and prevented from returning the kick; the ball must then be called down, which is a technical expression signifying a temporary suspension of hostilities in order to get the ball again in play. The middle rusher then takes the ball, and placing his foot upon it snaps it to the quarter-back or to one of the other rushers, but to whomever he may thus give it that player must pass it to still another before the ball can be run forward with. If in three consecutive downs by the same side that side does not advance the ball five or take it back twenty yards, the opposing side is then entitled to it, and as an aid in determining the distance parallel lines five yards apart are often marked across the field.

The game is commenced by placing the ball in the center of the field, and, if there be no wind, the side winning the toss choosing as a general thing to kick off. But if the wind be blowing, however slightly, the winner will of course play with the wind, for this is a most important factor in foot-ball, a stiff breeze deciding whether the game shall be a kicking or running one. We will suppose the ball has been kicked off and stopped by one of the opposing half-backs, this player tackled and prevented from returning the kick; the ball must then be called down, which is a technical expression signifying a temporary suspension of hostilities in order to get the ball again in play. The middle rusher then takes the ball, and placing his foot upon it snaps it to the quarter-back or to one of the other rushers, but to whomever he may thus give it that player must pass it to still another before the ball can be run forward with. If in three consecutive downs by the same side that side does not advance the ball five or take it back twenty yards, the opposing side is then entitled to it, and as an aid in determining the distance parallel lines five yards apart are often marked across the field.

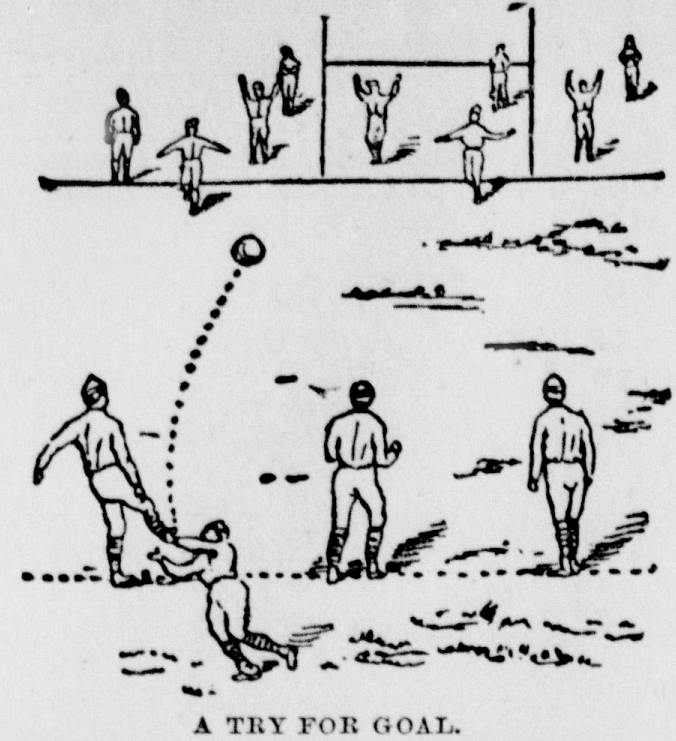

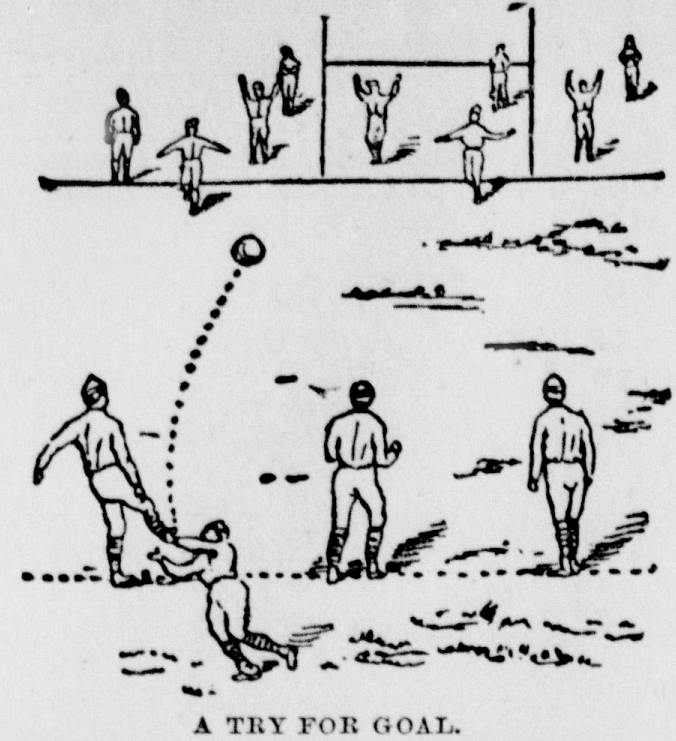

This is one of the new rules, and was introduced in order to diminish the chances of a draw game, which result could easily be brought about in the past where the strength of the competing teams was nearly equal. We will now suppose that the side kicking off has forced the ball ahead, and a player on that side succeeds in crossing the goal line and touches the ball on the ground; this is called a touch-down; then a player of the side scoring the touch-down, and called the placer, brings the ball out from the place where the touch-down was made, and at right angles to the goal line.

Having reached a suitable distance the placer, lying down and acting under the direction of the goal kicker, carefully poises the ball about an inch from the ground.

When the point of the ball is at the proper altitude, the seam in a line with the object point, and allowance made for the wind, the goal kicker gives the signal, the ball is placed on the ground, and the try for goal is made. The instant the ball touches the ground the opposing team may charge, and if the ball touches the person or clothing of any player before going over the cross-bar or posts the goal does not count; the slightest deviation made by the placer in putting the ball on the ground or failure of the goal kicker to kick in precisely the one correct spot will cause the ball to veer widely from the mark, and no goal is made.

If the goal counts the ball is brought to the center of the field, and the losing side kicks off. If the try for goal fails the other side kicks the ball out and must do so within the twenty-five yard line. Now, we will again suppose that one side has forced the ball up to the opponents’ goal, but instead of making a touch-down, as in the former case, they lose the ball. The other side, having gained possession of it, is of course in a much better position than before, but nevertheless still in great danger, for they in turn may lose it any instant. In this dilemma there is an avenue of escape, and that is by touching the ball down behind their own goal line and making what is termed a safety touch-down. Although this counts against it is not nearly so expensive as a touch-down by the other side.

If the goal counts the ball is brought to the center of the field, and the losing side kicks off. If the try for goal fails the other side kicks the ball out and must do so within the twenty-five yard line. Now, we will again suppose that one side has forced the ball up to the opponents’ goal, but instead of making a touch-down, as in the former case, they lose the ball. The other side, having gained possession of it, is of course in a much better position than before, but nevertheless still in great danger, for they in turn may lose it any instant. In this dilemma there is an avenue of escape, and that is by touching the ball down behind their own goal line and making what is termed a safety touch-down. Although this counts against it is not nearly so expensive as a touch-down by the other side.

The value of points in scoring is as follows:

- Goal from touch-down – 6

- Goal from field kick – 5

- Touch-down – 4

- Safety touch-down – 2

A drop-kick is made by letting the ball fall from the hands and kicking it the very instant it rises.

A drop-kick is made by letting the ball fall from the hands and kicking it the very instant it rises.

A place-kick is made by kicking the ball after it has been placed on the ground.

A punt is made by letting the ball fall from the hands and kicking it before it touches the ground; a goal made by a punt-kick does not count.

The time of a game is an hour and a half, each side playing forty-five minutes from each goal, with an intermission of ten minutes between the two halves.

No one is allowed to wear projecting nails or iron plates.

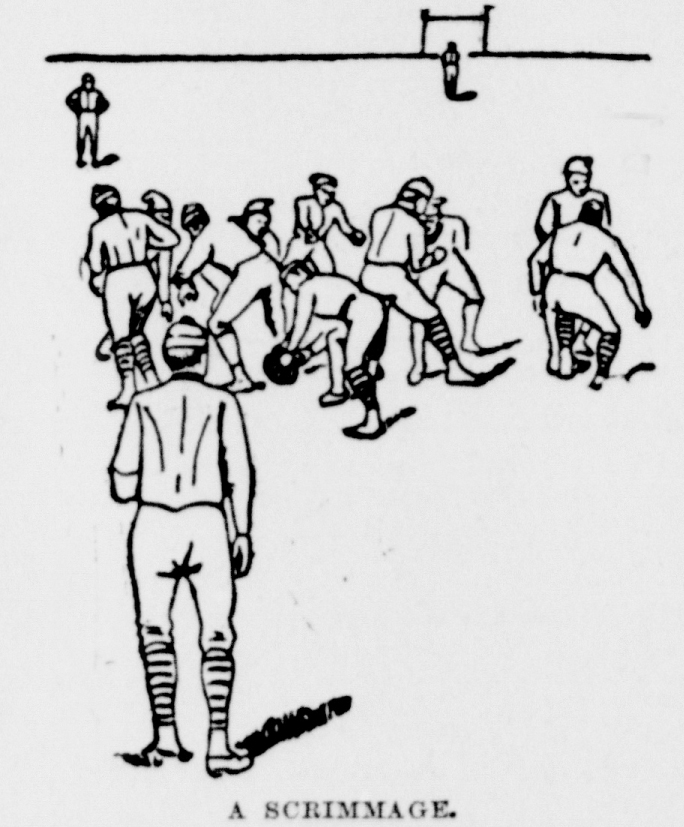

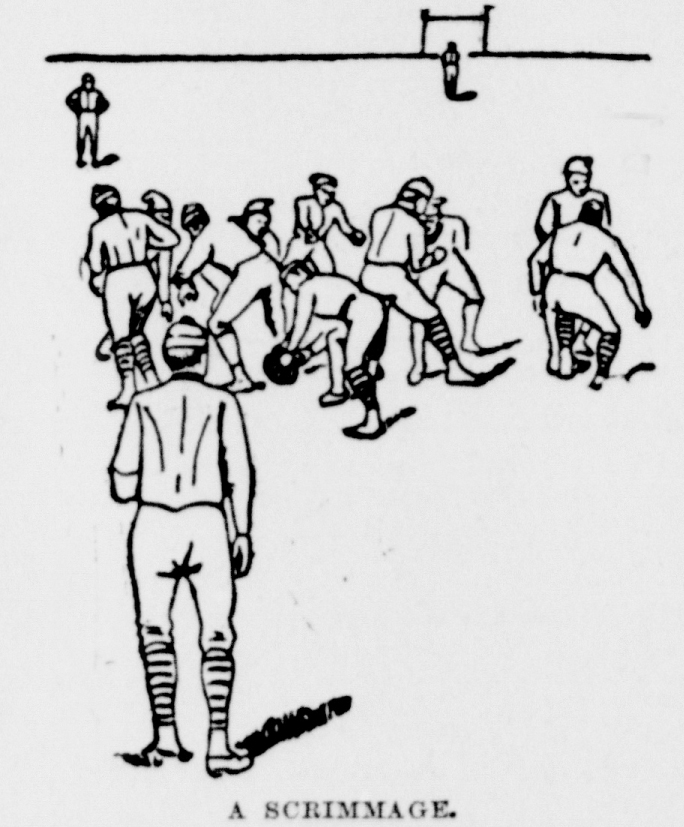

A scrimmage takes place when the holder of the ball places it on the ground and puts it in play by kicking it or snapping it back.

A player is off side if during a scrimmage he gets in front of the ball or if the ball has been last touched by his own side behind him, and when off side he is not allowed to touch the ball.

A player being off side is put on side when the ball has touched an opponent or when one of his own side has run in front of him either with the ball or having touched it when behind him.

No player shall interfere with an opponent in any way unless he has the ball.

A foul shall be granted for intentional delay of game, off-side play, or holding an opponent unless he has the ball; the penalty of a foul is a down for the other side.

A player shall be disqualified for unnecessary roughness, hacking, throttling, butting, tripping up, intentional tackling below the knees, and striking with the closed fists.

A player shall be disqualified for unnecessary roughness, hacking, throttling, butting, tripping up, intentional tackling below the knees, and striking with the closed fists.

In case a player be disqualified or injured a substitute shall take his place.

A player may throw or pass the ball in any direction except toward the opponents’ goal; it shall be given to the opponents if it be batted or thrown forward.

If the ball goes out of bounds a player on the side which touches it down must bring to the spot where it crossed the line, and there either bound the ball in the field of play or touch it with both hands at right angles to the line, and then run with it, kick it, or throw it back, or it may be thrown in at right angles or be taken out in the field of play at right angles to any distance not less than five nor more than fifteen yards, and there put down the same as for a scrimmage.

There is an umpire and also a referee.

The umpire is the judge for the players as regards fouls and unfair tactics.

The referee is judge in all matters relating to the ball, and all points not covered by the duties of the umpire.

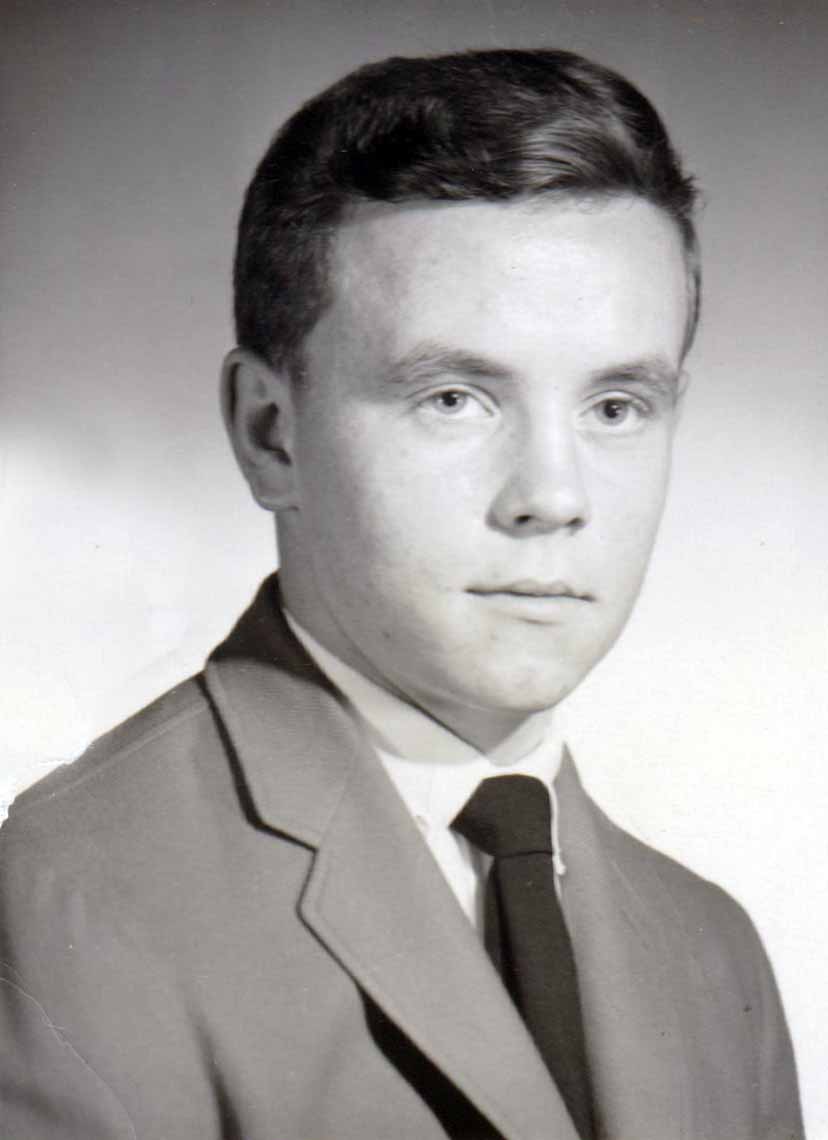

“Ruby” Ertle played both linebacker and lineman under Head Coach Bob Seaman. As a starter during his junior year he instantly became a force on defense, giving a hundred percent on every play. One could describe him as just a “really tough player.” Against Canton McKinley he had a pass interception to quell a drive, and also during the season recovered two fumbles. Unfortunately, the Tigers’ record that year was 4-5-1.

“Ruby” Ertle played both linebacker and lineman under Head Coach Bob Seaman. As a starter during his junior year he instantly became a force on defense, giving a hundred percent on every play. One could describe him as just a “really tough player.” Against Canton McKinley he had a pass interception to quell a drive, and also during the season recovered two fumbles. Unfortunately, the Tigers’ record that year was 4-5-1.

In

In

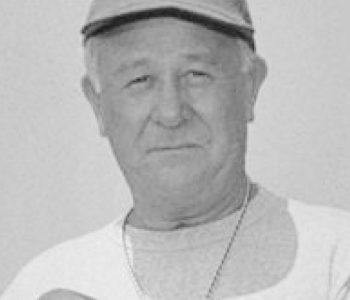

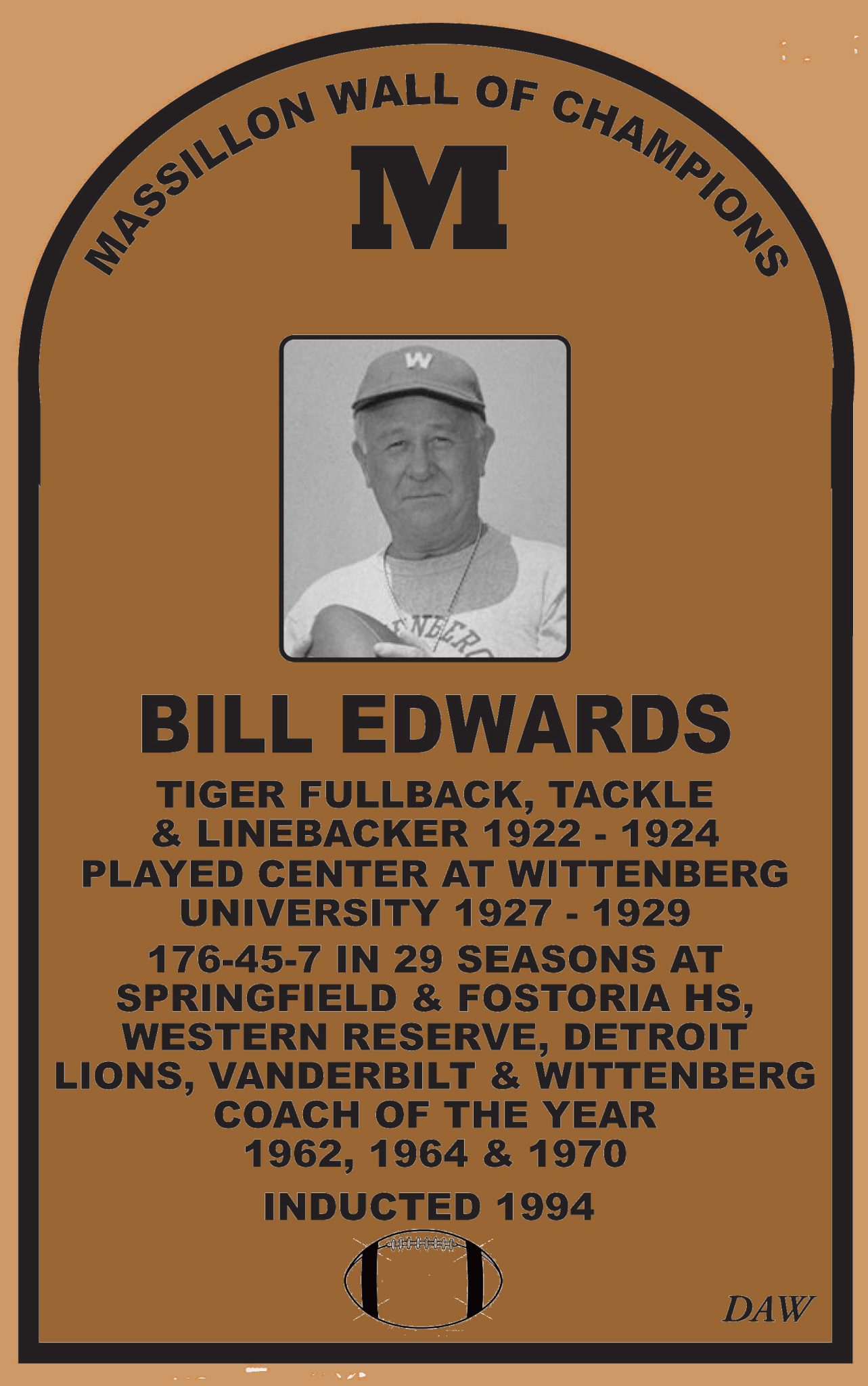

Springfield High School (1931) – Assistant coach and history teacher.

Springfield High School (1931) – Assistant coach and history teacher.

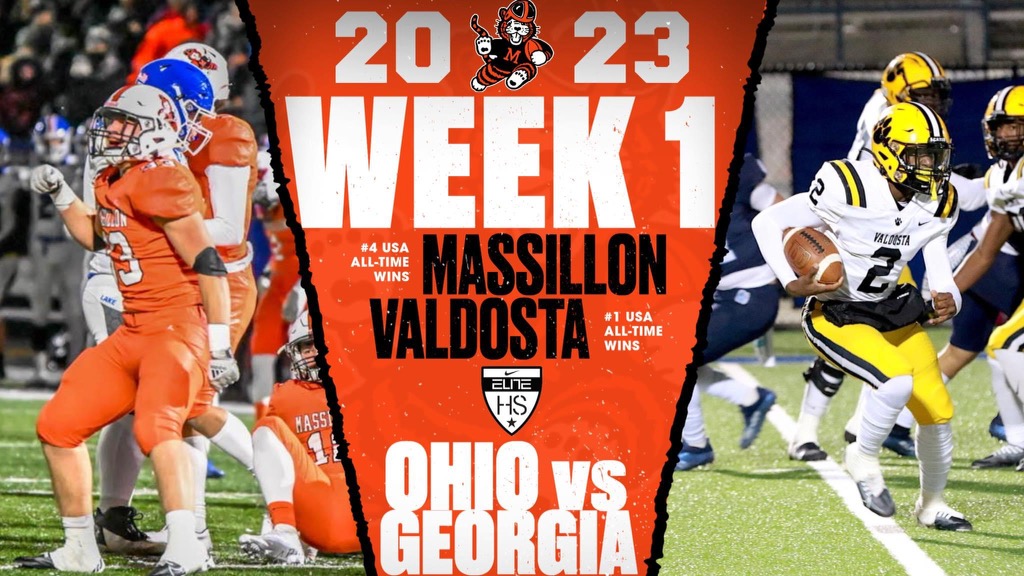

The game will be part of the

The game will be part of the  In 2022 Valdosta finished with a record of 8-3, losing 28-13 to Westlake in the first round of the state playoffs. Their record over the past five years is 33-26. Four times in that span they qualified for the playoffs and, as their best performance, advanced to the Division 6A state semifinals in 2020.

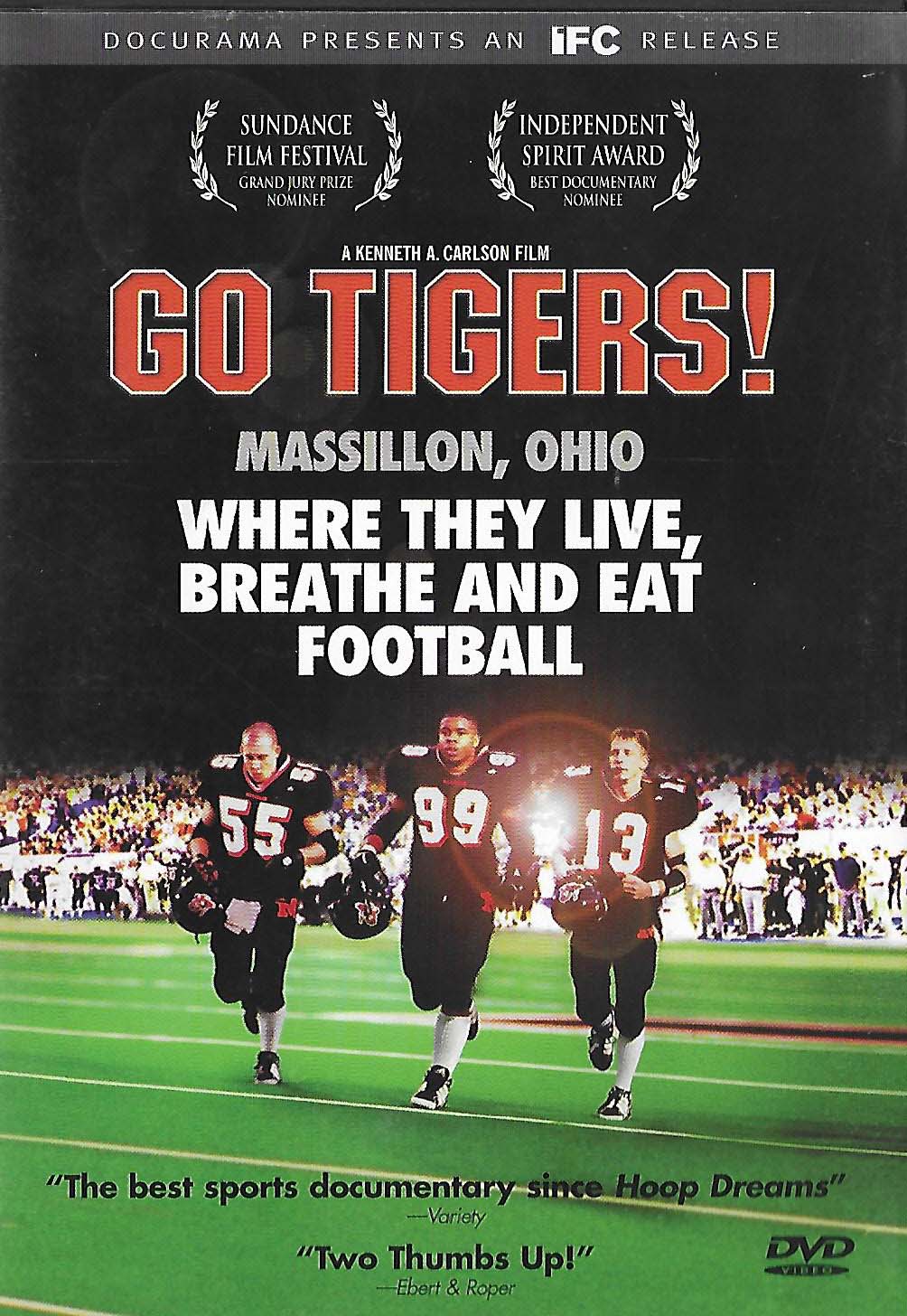

In 2022 Valdosta finished with a record of 8-3, losing 28-13 to Westlake in the first round of the state playoffs. Their record over the past five years is 33-26. Four times in that span they qualified for the playoffs and, as their best performance, advanced to the Division 6A state semifinals in 2020. Massillon owns an historical record of 932-338-32 and is currently fourth in the national rankings, one win behind Mayfield, Kentucky. The Tigers began playing football in 1891 and have won 9 national championships and 24 Ohio state championships (the most recent being in 1970). Twenty-three times they finished the regular season unbeaten. As the subject of numerous books and films, the most popular entry was the theater production, “Go Tigers,” which covered the 1999 season.

Massillon owns an historical record of 932-338-32 and is currently fourth in the national rankings, one win behind Mayfield, Kentucky. The Tigers began playing football in 1891 and have won 9 national championships and 24 Ohio state championships (the most recent being in 1970). Twenty-three times they finished the regular season unbeaten. As the subject of numerous books and films, the most popular entry was the theater production, “Go Tigers,” which covered the 1999 season.

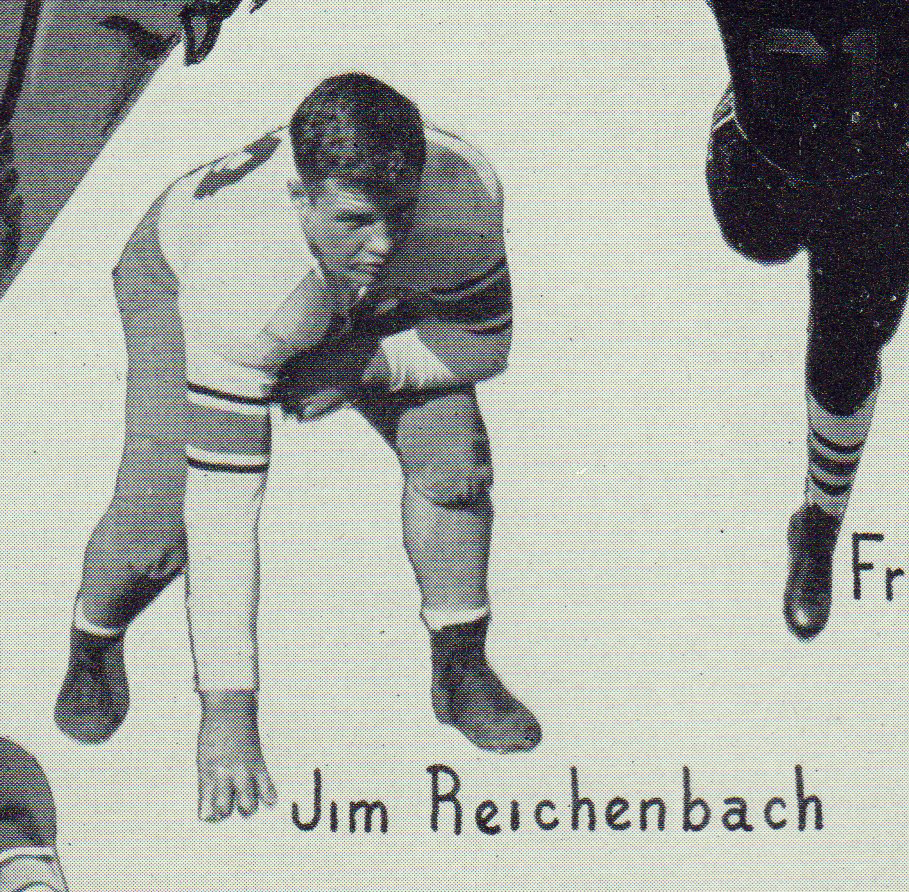

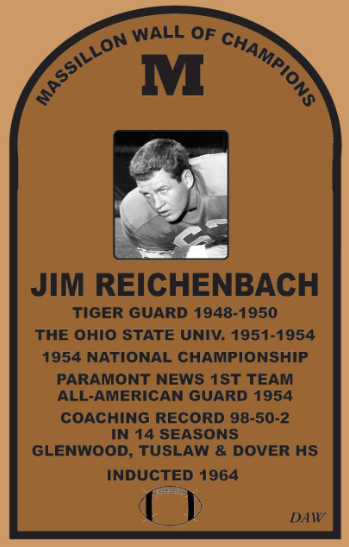

He was a bull of a player as recalled by Jim Schumacher (1948-50). “Reichenbach and I could work the blocking sled like a team of horses,” he said. “We hit that thing a lot. We could drive that baby 15 yards. We were good because we were a team.” – Massillon Memories, Scott Shook.

He was a bull of a player as recalled by Jim Schumacher (1948-50). “Reichenbach and I could work the blocking sled like a team of horses,” he said. “We hit that thing a lot. We could drive that baby 15 yards. We were good because we were a team.” – Massillon Memories, Scott Shook. 1951 – Record of 4-3-2. Lost to Michigan, 7-0.

1951 – Record of 4-3-2. Lost to Michigan, 7-0. “You grow up, and I don’t think I’ll ever change very much from when I was 16 years old playing for Coach Reichenbach,” said Pro Football Hall of Fame offensive lineman Dan Dierdorf, who played at Glenwood for Reichenbach. “I was deathly afraid of him. He looked to me … to be eight feet tall. He was an imposing guy.

“You grow up, and I don’t think I’ll ever change very much from when I was 16 years old playing for Coach Reichenbach,” said Pro Football Hall of Fame offensive lineman Dan Dierdorf, who played at Glenwood for Reichenbach. “I was deathly afraid of him. He looked to me … to be eight feet tall. He was an imposing guy.

The best player is not necessarily he who makes the longest runs or kicks, says the Chicago Inter Ocean, but the one combining good, hard individual play with team work, and is always willing to let the man make the brilliant play whose chances are the best. The training to thoroughly fit one’s self for a match game is as arduous as it is for a boat race; in addition to the daily practice, a run of two to three miles is necessary for the wind; smoking, drinking, pastry, and rich food must be given up, and plenty of sleep taken. Five minutes of brisk work will cause the player who enters a game in poor condition to make many good resolves for the future.

The best player is not necessarily he who makes the longest runs or kicks, says the Chicago Inter Ocean, but the one combining good, hard individual play with team work, and is always willing to let the man make the brilliant play whose chances are the best. The training to thoroughly fit one’s self for a match game is as arduous as it is for a boat race; in addition to the daily practice, a run of two to three miles is necessary for the wind; smoking, drinking, pastry, and rich food must be given up, and plenty of sleep taken. Five minutes of brisk work will cause the player who enters a game in poor condition to make many good resolves for the future. There are eleven men on a side, generally seven in the rush line, a quarterback, two half-backs, and a back. The prime qualifications of the rushers should be weight, strength, and endurance, for on them devolve the duty of forging ahead by running with the ball. They need know little or nothing about kicking, and should never touch foot to the ball except in case of a free kick. Even then it is not necessary, for a place kick can be taken instead by one of the other players, and is generally preferable. Weight is not so essential for the rest of the team, but in addition to the other qualifications of the rushes they must be good kickers; also they should be sure tacklers to stop an opponent if he succeeds in breaking through the rush line. The following diagram shows the relative position of the players:

There are eleven men on a side, generally seven in the rush line, a quarterback, two half-backs, and a back. The prime qualifications of the rushers should be weight, strength, and endurance, for on them devolve the duty of forging ahead by running with the ball. They need know little or nothing about kicking, and should never touch foot to the ball except in case of a free kick. Even then it is not necessary, for a place kick can be taken instead by one of the other players, and is generally preferable. Weight is not so essential for the rest of the team, but in addition to the other qualifications of the rushes they must be good kickers; also they should be sure tacklers to stop an opponent if he succeeds in breaking through the rush line. The following diagram shows the relative position of the players: The game is commenced by placing the ball in the center of the field, and, if there be no wind, the side winning the toss choosing as a general thing to kick off. But if the wind be blowing, however slightly, the winner will of course play with the wind, for this is a most important factor in foot-ball, a stiff breeze deciding whether the game shall be a kicking or running one. We will suppose the ball has been kicked off and stopped by one of the opposing half-backs, this player tackled and prevented from returning the kick; the ball must then be called down, which is a technical expression signifying a temporary suspension of hostilities in order to get the ball again in play. The middle rusher then takes the ball, and placing his foot upon it snaps it to the quarter-back or to one of the other rushers, but to whomever he may thus give it that player must pass it to still another before the ball can be run forward with. If in three consecutive downs by the same side that side does not advance the ball five or take it back twenty yards, the opposing side is then entitled to it, and as an aid in determining the distance parallel lines five yards apart are often marked across the field.

The game is commenced by placing the ball in the center of the field, and, if there be no wind, the side winning the toss choosing as a general thing to kick off. But if the wind be blowing, however slightly, the winner will of course play with the wind, for this is a most important factor in foot-ball, a stiff breeze deciding whether the game shall be a kicking or running one. We will suppose the ball has been kicked off and stopped by one of the opposing half-backs, this player tackled and prevented from returning the kick; the ball must then be called down, which is a technical expression signifying a temporary suspension of hostilities in order to get the ball again in play. The middle rusher then takes the ball, and placing his foot upon it snaps it to the quarter-back or to one of the other rushers, but to whomever he may thus give it that player must pass it to still another before the ball can be run forward with. If in three consecutive downs by the same side that side does not advance the ball five or take it back twenty yards, the opposing side is then entitled to it, and as an aid in determining the distance parallel lines five yards apart are often marked across the field. If the goal counts the ball is brought to the center of the field, and the losing side kicks off. If the try for goal fails the other side kicks the ball out and must do so within the twenty-five yard line. Now, we will again suppose that one side has forced the ball up to the opponents’ goal, but instead of making a touch-down, as in the former case, they lose the ball. The other side, having gained possession of it, is of course in a much better position than before, but nevertheless still in great danger, for they in turn may lose it any instant. In this dilemma there is an avenue of escape, and that is by touching the ball down behind their own goal line and making what is termed a safety touch-down. Although this counts against it is not nearly so expensive as a touch-down by the other side.

If the goal counts the ball is brought to the center of the field, and the losing side kicks off. If the try for goal fails the other side kicks the ball out and must do so within the twenty-five yard line. Now, we will again suppose that one side has forced the ball up to the opponents’ goal, but instead of making a touch-down, as in the former case, they lose the ball. The other side, having gained possession of it, is of course in a much better position than before, but nevertheless still in great danger, for they in turn may lose it any instant. In this dilemma there is an avenue of escape, and that is by touching the ball down behind their own goal line and making what is termed a safety touch-down. Although this counts against it is not nearly so expensive as a touch-down by the other side. A drop-kick is made by letting the ball fall from the hands and kicking it the very instant it rises.

A drop-kick is made by letting the ball fall from the hands and kicking it the very instant it rises. A player shall be disqualified for unnecessary roughness, hacking, throttling, butting, tripping up, intentional tackling below the knees, and striking with the closed fists.

A player shall be disqualified for unnecessary roughness, hacking, throttling, butting, tripping up, intentional tackling below the knees, and striking with the closed fists. All-Ohio Players from Tiger opponents:

All-Ohio Players from Tiger opponents: First Team

First Team Bob Commings was a very successful coach for the Tigers from 1969 to 1973, compiling a record of 43-6-2, including Massillon’s last state championship (1970) and qualification for Ohio’s first ever state playoff games (1972). Commings departed following the 1973 season to become head coach of the University of Iowa and later coached at GlenOak High School, for which their field was later named.

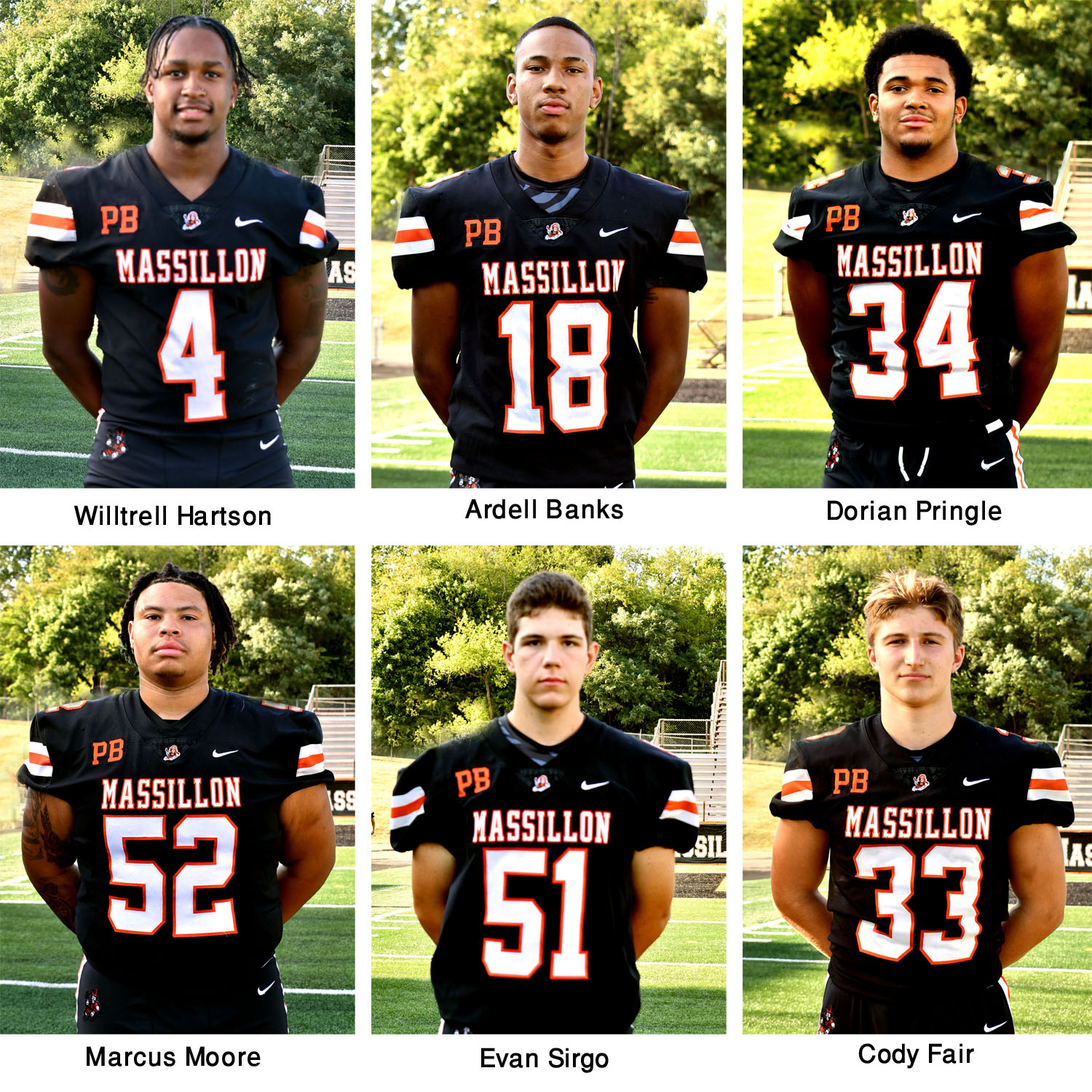

Bob Commings was a very successful coach for the Tigers from 1969 to 1973, compiling a record of 43-6-2, including Massillon’s last state championship (1970) and qualification for Ohio’s first ever state playoff games (1972). Commings departed following the 1973 season to become head coach of the University of Iowa and later coached at GlenOak High School, for which their field was later named. Left to right: Hardnose Award winner Willtrell Hartson, Touchdown Club President George Mizer, Head Coach Nate Moore, Assistant Coach and previous Hardnose Award winner Bo Grunder, defensive lineman Marcus Moore and long snapper Angelo Salvino.

Left to right: Hardnose Award winner Willtrell Hartson, Touchdown Club President George Mizer, Head Coach Nate Moore, Assistant Coach and previous Hardnose Award winner Bo Grunder, defensive lineman Marcus Moore and long snapper Angelo Salvino. Willtrell Hartson receiving the Hardnose Award from Bo Grunder.

Willtrell Hartson receiving the Hardnose Award from Bo Grunder. Willtrell Hartson and family

Willtrell Hartson and family