History

History Massillon’s History with a Theoretical 12-Team Playoff

Massillon’s History with a Theoretical 12-Team Playoff

“There’s no place like home,” Dorothy exclaimed near the end of the legendary movie, “The Wizard of Oz.” And Massillon Tiger football fans can say the same following the Ohio High School Athletic Association’s (OHSAA) decision to revamp the state football playoffs. With the change, in spite of fewer teams now qualifying, there are better opportunities to host post-season games.

The OHSAA’s playoff system used to determine football state championships was introduced in 1972 at the request of the association coaches. But inspite of the great intentions the OHSAA had at the time, it was not an optimal system at the start and a host of changes have occurred since that time. Initially, just one team qualified from each of four regions across three divisions. In 1980 two more divisions were added and the number of qualifiers per region doubled. In 1985 it became four teams per region, followed in 1994 by the addition of a sixth division. Four per region became eight in 1999 and a seventh division was added in 2013. Whew! That’s a lot of changes.

But it might have remained that way, except that the Covid year of 2020 messed it all up. On account of several canceled games due to the impact of the ailment and the resulting difficulty in selecting qualifiers, the OHSAA opened the door to every team in the state. The following year, with the OHSAA believing that it was beneficial for many schools to enhance the number of participants, the number of regional qualifiers was increased to sixteen. Not discussed was the additional revenue afforded to the OHSAA from the additional 112 games across the seven divisions, considering that the OHSAA also at that time took over control of sales and collection of money from the purchase of playoff game tickets.

Regardless of the OHSAA’s beliefs, the coaches apparently were never in favor of a 16-team region, preferring twelve instead, with the top four qualifiers receiving byes in the first round. It should be noted that a 12-team format was the format going into the 2020 season until it was derailed by Covid. Now finally, the coaches have gotten their way.

Per this author, the right number is probably eight teams per region. However, the method used to select the teams, i.e., the Harbin System, has several flaws and is considered incapable of selecting these eight teams, let alone seeding them properly, as compared to algorithm-based methods that utilize true strength-of-schedule components, not just a simple summation of opponent wins. For, all teams are just not created equal. The author’s study shows that, in order to assure that the best eight teams are included, at least twelve teams from the Harbin System must be selected. Thus, a 12-team format is therefore considered optimal, although it doesn’t solve the seeding problem and corresponding earned rights to home games.

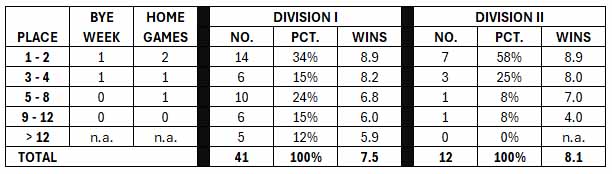

With the recent modification, the top four seeded teams receive a bye in the first round. The remaining teams face off, with 5 vs. 12, 6 vs. 11, 7 vs. 10 and 8 vs. 9. In Round 2, No. 1 faces the winner of 5 vs. 12, No. 2 faces the winner of 6 vs. 11, etc. The next two weeks are then used to determine the regional champion. In Weeks 1-3 the higher-seeded team hosts the game. The Week 4 championship game is then played at a neutral site.

With this format, the ideal seeded positions are Nos. 1 and 2. Not only do these teams receive a bye week, they are also guaranteed the potential of two home games. The next favorable positions are Nos. 3 and 4. These teams receive a bye week plus one guaranteed home game. After that comes Nos. 5-8, with one guaranteed home game.

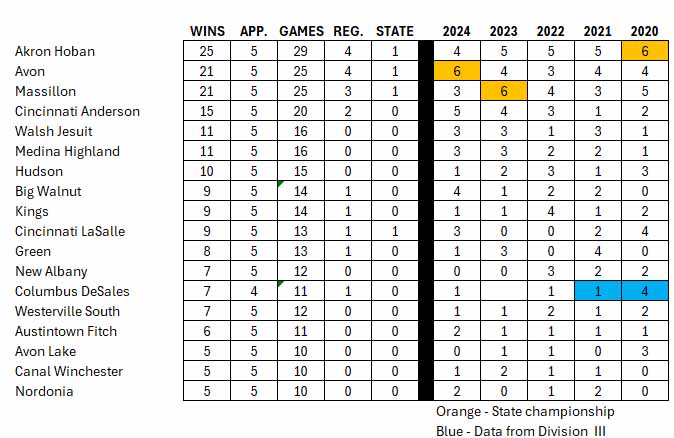

Now for the fun part. Had the new playoff format been in place since the start of the playoffs in 1972, a span of some 53 years, how would Massillon have faired year-to-year? The chart below presents the raw numbers.

The Tigers were in Division I from the start through 2012. The data shows that they would have qualified for the playoffs 36 times out of 41 attempts, or 88% of the time. Of the five years in which they failed to qualify, twice (1998 and 2004) they had four wins and twice (1974 and 2007) they had six wins, so that’s understandable. Ironically, they would have qualified in every year under a 16-team format.

The outlier came in 1978 when Massillon finished in the 14th position with a record of 9-0-1 and would have failed to qualify. Again, the flaws of the Harbin System are cited. The problem that year was with the opponents, most of which failed to win many games. In fact, outside of Canton McKinley (7-2) and Warren Harding (7-2-1), the remaining teams won just a third of their games, something the Tigers had no control over. Of course, there were only three divisions at that time. In a 7-division format they would most likely have qualified.

About a third of the time they would have been seeded first or second. They would have finished in the top four and received a first-round bye 20 times, or about half. And they would have finished in the top eight and hosted at least one game 30 times, or about three-quarters.

In 2013 the divisions were restructured, with the Tigers assigned to Division II, since the number of teams placed in Division I was lowered. Over the next twelve years Massillon would have qualified in every year. Seven times, or 58%, they would have been seeded first or second. They would have received a first-round bye ten times, or 83%. And they would have hosted at least one game eleven times or 92%. The only year in which they would not have hosted a game was in Coach Nate Moore’s first year, when the team finished in 11th place with a record of 4-6. However, the playoffs would have been interesting that year, given that Massillon defeated eventual regional champion Perry during the regular season.

Thus, if Massillon’s success over the past several years continues, there is a high probably of having a bye in the first round of the playoffs, something that is beneficial for three reasons. The first is that it provides the program a chance to regroup both physically and mentally following an intense rivalry game. Second, they could reach the finals while playing one less game than previously. And third, they could continue to have a high probability of hosting two playoff games. Because, let’s face it; there’s no place like home!

His stint in the minor leagues lasted just two years, before he was promoted to the majors as a National League umpire. He worked his first game (Brooklyn Dodgers vs. Chicago Cubs) on September 27, 1906, at age 24, thereby becoming the youngest umpire in Major League history. He remained there for thirty years (1906 thru 1935), umpiring 4,144 regular season games, a mark that was ranked fourth all-time when he retired. He was also behind the plate for 2,468 of those games. So well respected was Rigler, that he was also selected to umpire in ten different World Series, involving 65 games. He also umpired in the first All-Star Game, in 1933. Rigler’s last outing was on September 29, 1935. Following the season. he was placed on the supervisory staff of the National League and named Chief of Umpires. But unfortunately, he passed away before he could assume the role.

His stint in the minor leagues lasted just two years, before he was promoted to the majors as a National League umpire. He worked his first game (Brooklyn Dodgers vs. Chicago Cubs) on September 27, 1906, at age 24, thereby becoming the youngest umpire in Major League history. He remained there for thirty years (1906 thru 1935), umpiring 4,144 regular season games, a mark that was ranked fourth all-time when he retired. He was also behind the plate for 2,468 of those games. So well respected was Rigler, that he was also selected to umpire in ten different World Series, involving 65 games. He also umpired in the first All-Star Game, in 1933. Rigler’s last outing was on September 29, 1935. Following the season. he was placed on the supervisory staff of the National League and named Chief of Umpires. But unfortunately, he passed away before he could assume the role. He was considered as a very fair umpire and rarely needed to argue with either a coach or a player. But there was one particular exception in 1915 when he overruled another umpire’s call involving Reds’ Tommie Leach, who was caught off second base as the victim of a hidden-ball trick. The field umpire called Leach safe. Only Rigler, who from behind home plate had a better view of the play, called him out. Reds’ manager Buck Herzog quickly left the bench and approached Rigler to argue, shoving Cy in his chest protector and spiking his foot. So Rigler responded by putting Herzog on the ground with a single punch to the left eye. That set off a riot involving both players and fans, necessitating a dozen policemen to restore order. At the end of the day, both combatants found themselves in St. Louis Police Court and were fined $5.00 each.

He was considered as a very fair umpire and rarely needed to argue with either a coach or a player. But there was one particular exception in 1915 when he overruled another umpire’s call involving Reds’ Tommie Leach, who was caught off second base as the victim of a hidden-ball trick. The field umpire called Leach safe. Only Rigler, who from behind home plate had a better view of the play, called him out. Reds’ manager Buck Herzog quickly left the bench and approached Rigler to argue, shoving Cy in his chest protector and spiking his foot. So Rigler responded by putting Herzog on the ground with a single punch to the left eye. That set off a riot involving both players and fans, necessitating a dozen policemen to restore order. At the end of the day, both combatants found themselves in St. Louis Police Court and were fined $5.00 each.

Single season solo tackles, total tackles and tackle points – In 1982 Spielman in 13 games recorded 113 solo tackles and 43 assists, totaling 156 total tackles and 5 tackle points. He also had four pass interceptions and recovered two fumbles. Following the season he was named 1st Team All-Ohio at linebacker. The Tigers finished the year with a 12-1 record and advanced in the playoffs to the Division I state finals. Although Spielman wasn’t the fastest player on the field, his ability to read the play prior to the snap based on the opponent’s formation and also anticipate of the flow of the play when it began was perhaps unmatched by any previous Massillon player.

Single season solo tackles, total tackles and tackle points – In 1982 Spielman in 13 games recorded 113 solo tackles and 43 assists, totaling 156 total tackles and 5 tackle points. He also had four pass interceptions and recovered two fumbles. Following the season he was named 1st Team All-Ohio at linebacker. The Tigers finished the year with a 12-1 record and advanced in the playoffs to the Division I state finals. Although Spielman wasn’t the fastest player on the field, his ability to read the play prior to the snap based on the opponent’s formation and also anticipate of the flow of the play when it began was perhaps unmatched by any previous Massillon player.

Single season pass interceptions – In 2002 Relford intercepted 12 passes to set the single-season record. Four of the picks came against North Canton Hoover during a 31-0 playoff game victory. Included in that was returned 50-yard return for a score. He also ran back an interception 80 yards for TD against Cleveland St. Ignatius. The Tigers finished 12-3 that year and advanced in the playoffs to the Division I state semifinals.

Single season pass interceptions – In 2002 Relford intercepted 12 passes to set the single-season record. Four of the picks came against North Canton Hoover during a 31-0 playoff game victory. Included in that was returned 50-yard return for a score. He also ran back an interception 80 yards for TD against Cleveland St. Ignatius. The Tigers finished 12-3 that year and advanced in the playoffs to the Division I state semifinals. Career assisted tackles and total tackles – During his 3-year career Leno, playing at linebacker, recorded 123 solo tackles and 173 assisted tackles, for a total of 296 tackles. He also had 21 tackles for loss. His most productive games came in 2009 against Steubenville (11 solos, 4 assists) and Cleveland St. Ignatius (6 solos, 7 assists). Following the 2009 10-4 season Leno was named Special Mention All-Ohio.

Career assisted tackles and total tackles – During his 3-year career Leno, playing at linebacker, recorded 123 solo tackles and 173 assisted tackles, for a total of 296 tackles. He also had 21 tackles for loss. His most productive games came in 2009 against Steubenville (11 solos, 4 assists) and Cleveland St. Ignatius (6 solos, 7 assists). Following the 2009 10-4 season Leno was named Special Mention All-Ohio. Single game total tackles – In 1950 in a game against Warren Harding, Vliet recorded an unbelievable 42 tackles. Vliet’s asset was that he was incredibly adept at finding the ball carrier during the play, whether it was a running back or a receiver. So for this game, Head Coach Chuck Mather told Vliet that he wanted him to make all of the tackles. Meanwhile, the remaining ten players were instructed to prevent the Harding players from blocking Vliet. The ploy worked and the Tigers went on to win 23-6.

Single game total tackles – In 1950 in a game against Warren Harding, Vliet recorded an unbelievable 42 tackles. Vliet’s asset was that he was incredibly adept at finding the ball carrier during the play, whether it was a running back or a receiver. So for this game, Head Coach Chuck Mather told Vliet that he wanted him to make all of the tackles. Meanwhile, the remaining ten players were instructed to prevent the Harding players from blocking Vliet. The ploy worked and the Tigers went on to win 23-6. Single game quarterback sacks – In the 2005 season opener against Dover, McCall set a single-game record with 5 quarterback sacks. He also had 8 solo tackles and one assist, with 2.0 tackles for loss. Massillon won the game, 34-0. By season’s end, McCall led the team in total tackles, tackles for loss and quarterback sacks. He was also named 2nd Team All-Ohio. As a team, the Tigers finished 13-2 and advanced in the playoffs to the Division I state finals.

Single game quarterback sacks – In the 2005 season opener against Dover, McCall set a single-game record with 5 quarterback sacks. He also had 8 solo tackles and one assist, with 2.0 tackles for loss. Massillon won the game, 34-0. By season’s end, McCall led the team in total tackles, tackles for loss and quarterback sacks. He was also named 2nd Team All-Ohio. As a team, the Tigers finished 13-2 and advanced in the playoffs to the Division I state finals. Single game pass interceptions – In Game 2 of the 2005 season Massillon traveled south to face Cincinnati Elder in Paul Brown Stadium. Defensive back Troy Ellis had a career day against the Panthers by intercepting 5 passes. He also returned a fumble 25 yards for a score. Massillon led 35-7 at the end of the third quarter, but managed to hold on to win, 35-31.

Single game pass interceptions – In Game 2 of the 2005 season Massillon traveled south to face Cincinnati Elder in Paul Brown Stadium. Defensive back Troy Ellis had a career day against the Panthers by intercepting 5 passes. He also returned a fumble 25 yards for a score. Massillon led 35-7 at the end of the third quarter, but managed to hold on to win, 35-31. Single season assisted tackles – In 2018 Krichbaum recorded 78 assisted tackles in a 15-game season. He also led the team that year with 119 total tackles and 80.0 tackle points, with 10.5 tackles for loss. As a team Massillon was perfect in the win-loss column until the Division II state finals.

Single season assisted tackles – In 2018 Krichbaum recorded 78 assisted tackles in a 15-game season. He also led the team that year with 119 total tackles and 80.0 tackle points, with 10.5 tackles for loss. As a team Massillon was perfect in the win-loss column until the Division II state finals. Single season tackles for loss – In 2023 Pringle recorded 24.5 tackles for loss, while also finishing second in total tackles and quarterback sacks. His 2023 record erased the previous mark of 21.5, which he also set in 2022. His fortes were the abilities to find the ball in a crowd to make the tackle and also exhibit a ferocious pass blitz. Simply put, he was a “player,” along the lines of a Chris Spielman.

Single season tackles for loss – In 2023 Pringle recorded 24.5 tackles for loss, while also finishing second in total tackles and quarterback sacks. His 2023 record erased the previous mark of 21.5, which he also set in 2022. His fortes were the abilities to find the ball in a crowd to make the tackle and also exhibit a ferocious pass blitz. Simply put, he was a “player,” along the lines of a Chris Spielman.