History

History The Changing Landscape of Massillon Football – Part 7:…

The Changing Landscape of Massillon Football – Part 7: Game Attendance

This is the last entry of a 7-part series, which includes the following installments:

- Part 1: Offensive Formations

- Part 2: Defensive Formations

- Part 3: Passing Frequency

- Part 4: Scheduling

- Part 5: Roster Size

- Part 6: Stadiums

- Part 7: Game Attendance

Introduction

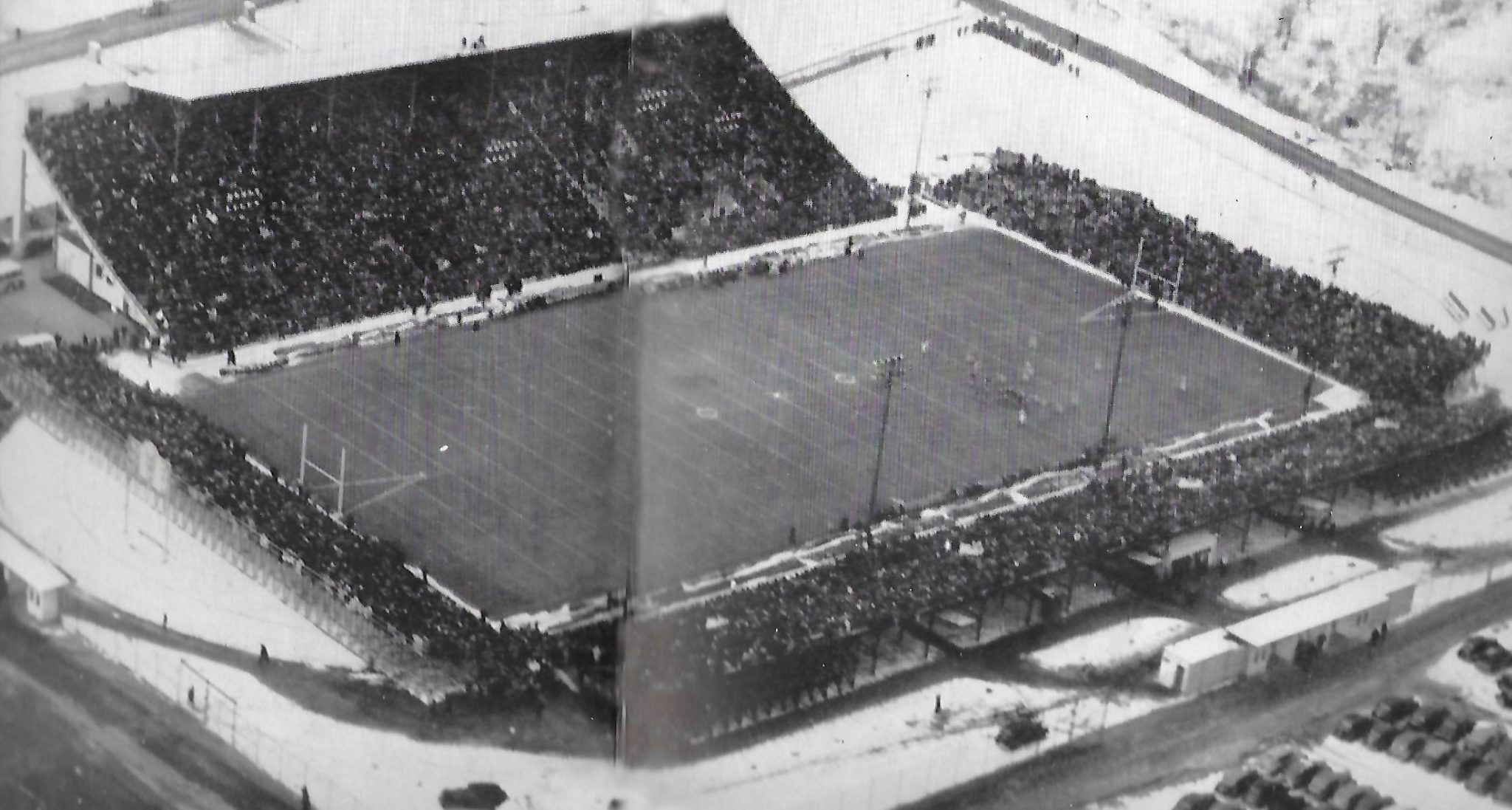

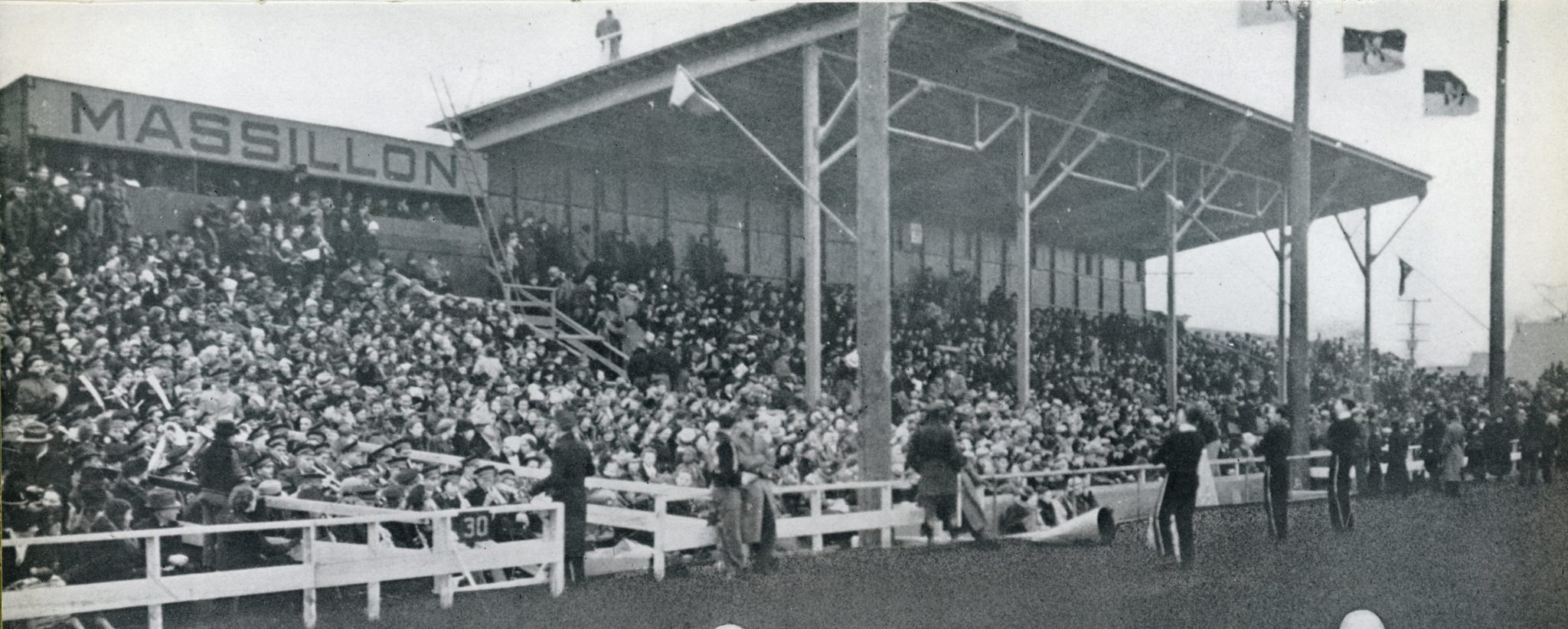

“With an overflow crowd of 15,000 spectators looking on, the Washington high school Tigers … opened their fine new football plant with a 40-13 triumph over a plucky Cathedral Latin high school team of Cleveland.” Those were the words of legendary sportswriter Luther Emery as he opened his story that covered the first game of the 1939 football season. It ever in the new Tiger Stadium and a capacity crowd was on hand to witness the event. Glowingly, it was far cry from the paltry crowds of just a few decades before.

Tiger Stadium would grow in size a few years later in order to accommodate crowds of nearly 20,000 each and every week. But the circus-like spectacle would not last. For various reasons, the average season attendance at Massillon games would slowly but steadily decline from then on to the present day.

Throughout its long history Massillon has played home games at eight different fields and the capacity limits of these venues have certainly had an influence on the number of fans that could attend. While most of the early fields had a small number of portable bleachers, the capacity increased exponentially when Massillon Field with 6,500 seats and then Tiger Stadium were built. A complimentary influence on crowd size was the instant success that the team achieved when Paul Brown became the coach. Suddenly, patrons were flocking to the games in droves. Thus, the need for a larger stadium.

Part 7 of the series takes a look back at the attendance at some of Massillon’s early games and then the seasonal averages from 1940 and on. It also presents the trends associated with the attendance at Massillon-McKinley games after Tiger Stadium and Canton’s Fawcett Stadium were opened.

The Early Years (1891-1923)

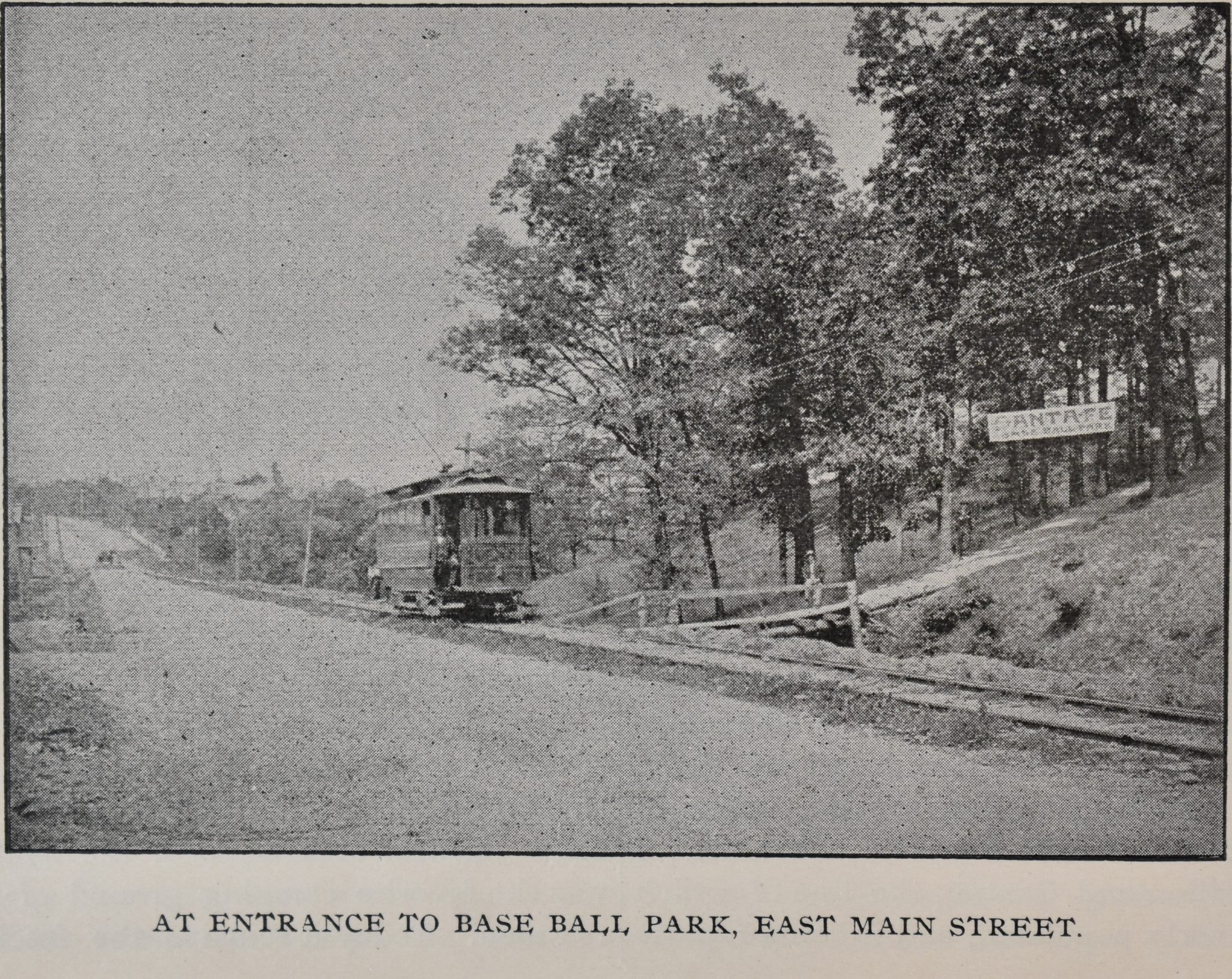

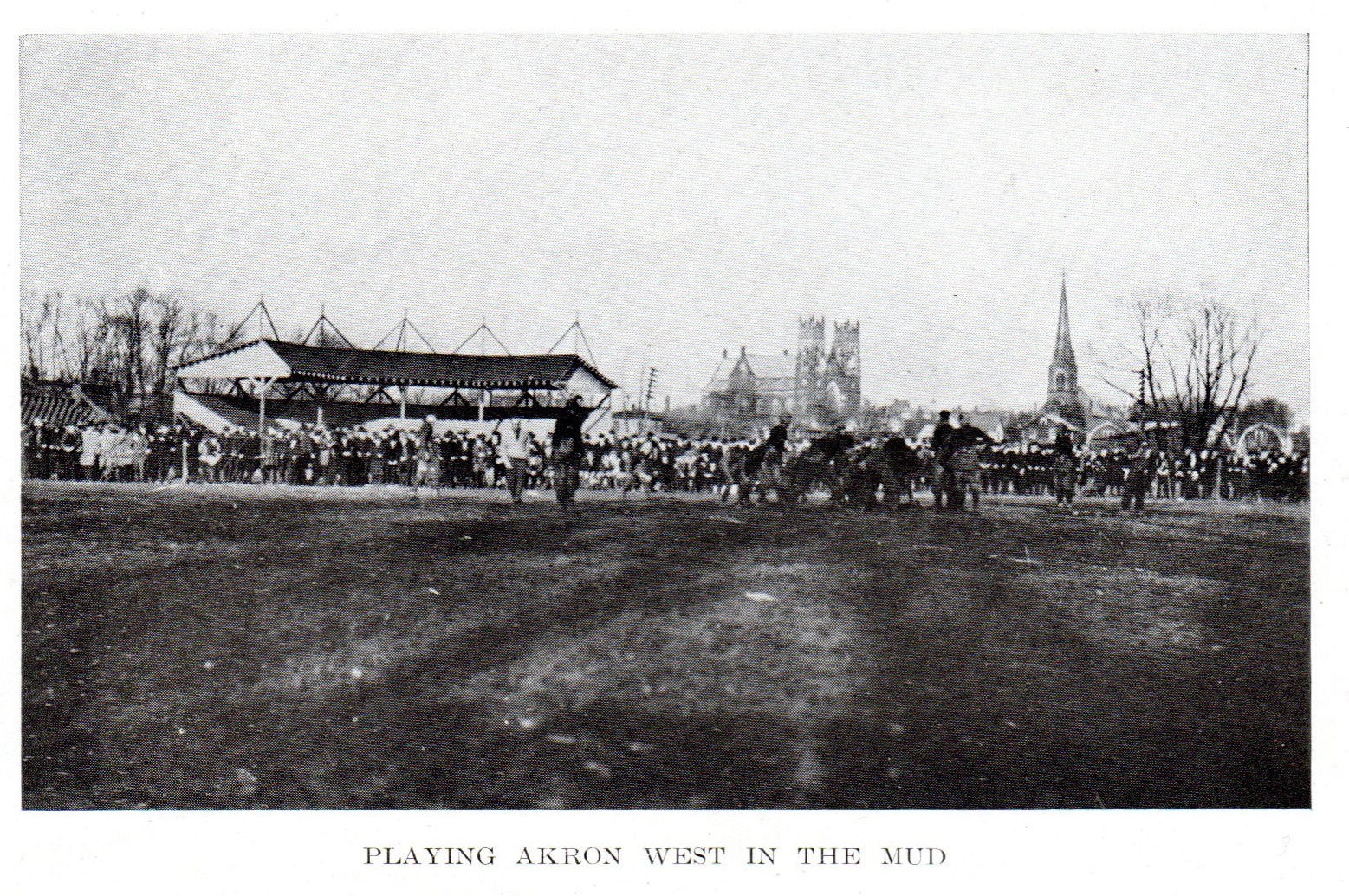

The first time the local media recorded the attendance for a Massillon home game was in 1894 when 200 fans attended a match against Canton Central, later to be named Canton McKinley. The contest was most likely played either on a Saturday or Friday afternoon, since there were no stadium lights at that time. And perhaps most of the attendees were high school students.

By 1908, 1,000 fans were in the North Street Field stadium to watch the Tigers defeat Alliance, 64-0. The following year, when Massillon captured its first state title, it was a throng of 2,000 patrons that witnessed a 9-0 win over Oberlin Academy, with everyone returning the following week to enjoy a 21-5 victory over New Philadelphia.

Home attendance continued to increase thereafter, particularly when the team played at Jones Field on Pearl Street. A crowd of 3,000 attended the 1920 Toledo Scott game, 6,000 were at the 1922 Cleveland Shaw game and 8,000 showed up for the 1924 game against McKinley. Suddenly, it was time for a bigger stadium.

Meanwhile, Tiger road games also saw an explosion in attendance numbers: 9,500 at the 1925 Canton McKinley game, 10,000 at the 1932 Alliance game, 10,000 at the 1933 McKinley game and 12,000 at the 1935 McKinley game.

Massillon Field (1924-38)

In 1924 Massillon opened a new stadium, one with permanent seating and a capacity of 6,500. It also had lights to accommodate night games. On occasion, additional portable seating would be brought in for a major opponent that boosted the capacity to 8,000 or more. But by 1935, when Brown was coach, the average home attendance swelled well above the 6,500 seat capacity. And in 1938, the last year of Massillon Field, the average home attendance was a whopping 11,500, with 18,000 squeezing in for the game against McKinley. Fortunately, by then, construction a new stadium was well underway.

The Tigers would leave Massillon Field with a home record of 71-16-4. Brown’s mark there was 41-4-2.

Paul Brown Tiger Stadium (1939 to present)

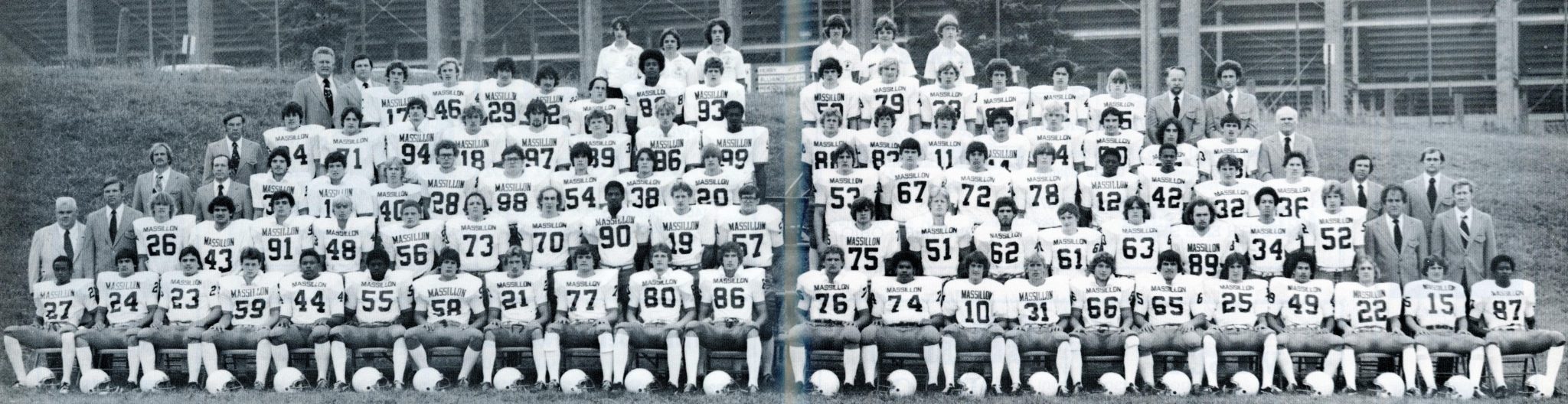

Tiger Stadium, later named after Paul Brown, opened in 1939 with a seating capacity of 14,000. It would soon be increased, including temporary sideline and end zone seats, to 22,500. Now Massillon had a stadium large enough to accommodate any football crowd. After some eighty years of use, Massillon’s current record there sits at 526-90-6.

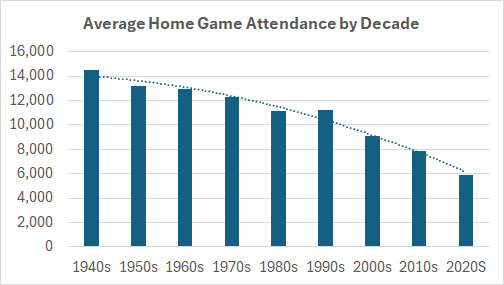

Home attendance was immediately impacted in that 1939 season with an average attendance of 13,200. The following year, owing to a home game against McKinley, the average was 17,450, a number that has stood since as an all-time record. Below is a chart of the average home attendance by decade from 1940 to the present.

In the decade of the 1940s, the average home attendance was 14,476. But that number has steadily declined over time and now stands at 5,901, although perhaps still higher than any other school in the state. There are perhaps several reasons for this trend:

- Advent of television – TV was not prevalent throughout households in the 1940s, so high school football was akin to the circus coming to town and most city residents flocked to local stadiums for an evening’s entertainment. Massillon was no different. This was especially true with the tremendous program left in place by Coach Paul Brown, who departed in 1941 for Ohio State. Although Massillon’s high level of success has continued into the present day, the attendance has not kept pace. In the 1950s televisions found their way into American homes, and even in Massillon the phenomenon created competition for high school football on Friday nights. The impact was felt again in the mid-1960s when Massillon Cable TV was introduced and it began airing delayed broadcasts of the games.

- Opening of schools adjacent to Massillon – In the 1940s Massillon students resided not only in Massillon proper, but also in areas surrounding the city. However, in 1956 Perry High School was opened, followed shortly thereafter by Jackson and Tuslaw. Over time, all served to shrink the total area from which Massillon High School drew both students and sports fans.

- Dissolution of the All-American Conference – In 1963 a league consisting of some of the top teams in Ohio (Massillon, Canton McKinley, Warren Harding and Niles) was formed. The addition of Steubenville in 1966 and Alliance in 1969 only made the league more prominent. Games against these rivals created tremendous fan interest and provided some of the most competitive and highly-attended games in the state. Because of this, attendance at Massillon games remained fairly steady during the 1960s and 1970s. But by the late 1970s, Niles, Steubenville and Alliance could not maintain competitiveness due to declining enrollment as a result of the steel mills closing and the All-American Conference played its final games in 1979. This consequence brought an immediate drop in fan attendance as league games one by one vacated the schedule.

- Declining enrollment – The 1980s also saw Massillon’s enrollment begin a steady decline, now leveling off at about 30% less. Although having modest impact on attendance, there are now somewhat less students and associated parents attending the games.

- Recession – The early 2000s brought the onset of an economic recession, which impacted the job prospects and incomes of many workers in Massillon. There was an obvious need for families to trim their household budgets and football tickets may have been one of the first items to go. The result was the largest decline in attendance, from 11,229 in the 1990s to 9,125 in the 2000s, or a reduction of 19%.

- Aging Fans – Many fans in the 1940s, 50s and 60s were captivated by the success of the football team and continued to remain loyal to the program for many years thereafter, always hopeful of yet another state championship. However, there comes a time when a person is just too old to attend the games. Fans that were in their 20s during the 1940s are now aging out. To maintain the attendance level their losses needed to be recouped by younger fans. Unfortunately, young fans in the 1970s and beyond did not get to experience those championship years and are not as prone to embrace the football program and purchase tickets after graduation.

Games Against Canton McKinley

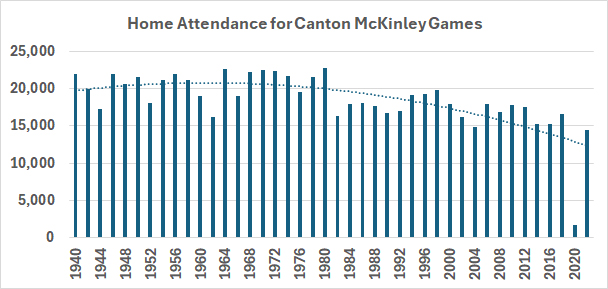

The attendance for the McKinley games has also seen a reduction, although of a different sort. Rather than a constant decline, there was a step change for home games beginning in 1982. From 1940 to 1980, the average attendance was 20,752. Afterwards, it has been 17,146 (not including the Covid year of 2020), or a decline of 17%. In addition, last year’s attendance of 14,474 was the lowest home attendance for this game since 1926 (not counting the Covid year).

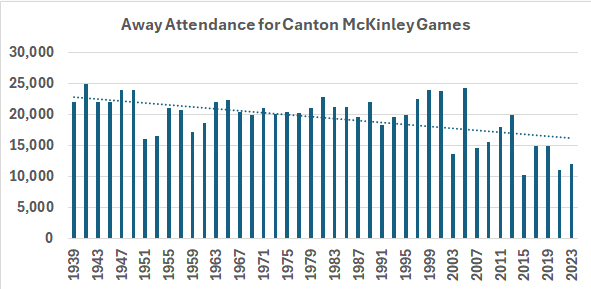

In case you were wondering about games in Canton, there was a similar step change, but theirs did not occur until 2007. From 1939 to 2005, the average was 20,883. Since then, it has been 14,610, or a decline of a whopping 30%. Also, the attendance of 2023 was 42% below the prior number.

Best Attended Home Games

It’s no secret that the best attended games are those against McKinley. Over the past thirty years these contests have drawn on average over 16,000 fans. Next up are the games against the large parochial schools, followed by the season openers. For the openers, it’s the anticipation of a new season and the weather is warm. And of late the competition has been high-caliber. Below are the 30-year averages for various categories:

- 17,200 – Canton McKinley

- 12,351 – Large Parochial Schools

- 10,075 – Season Opener

- 9,388 – Rival Public Schools

- 8,432 – Mid-size Parochial Schools

- 8,231 – Non-rival Public Schools

- 8,777 – Out-of-state

- 8,352 – Playoffs

Attendance Records

The home record for attendance was set in 1964 when 22,685 fans attended the game against McKinley. The Tigers won that one 20-14. Just behind are the 1972 game, which drew 22,371, and the 1968 game, which drew 22,305, followed by four games in which the estimated crowd was 22,000.

On the road, the Number One attended game was against Cleveland Cathedral Latin in 1945, which was held at Cleveland Municipal Stadium. The final score was 6-6. Here are the Top 5:

- 51,409 – 1945 – Cleveland Municipal Stadium – Cleveland Cathedral Latin

- 33,000 – 1940 – Akron Rubber Bowl – Alliance

- 31,409 – 1982 – Ohio State Stadium – Cincinnati Moeller (playoffs)

- 30,129 – 1964 – Akron Rubber Bowl – Niles McKinley

- 29,871 – 2001 – Akron Rubber Bowl – Cleveland St. Ignatius (playoffs)

Summary

The average seasonal attendance at Massillon home games has declined steadily over the past eighty years for a number of reasons. But that does not deter a sizeable number of Tiger fans from still attending the games. For Massillon continues to outdraw every other school in Ohio. Nevertheless, there still seems to be a measurable decline as of late in attendance for the McKinley game. But this may have been influenced more by Canton’s declining support of the game than by Massillon’s, as evidenced by the 2023 game in Canton in which the Tigers outdrew the Bulldogs in their own stadium.

At times the attendance, and particularly season ticket sales, has seen a bump the following year when the Tigers win a championship or even when they advance in the playoffs to the state finals. It will be interesting this year to see how it plays out with Massillon fresh off of a Division II state championship.

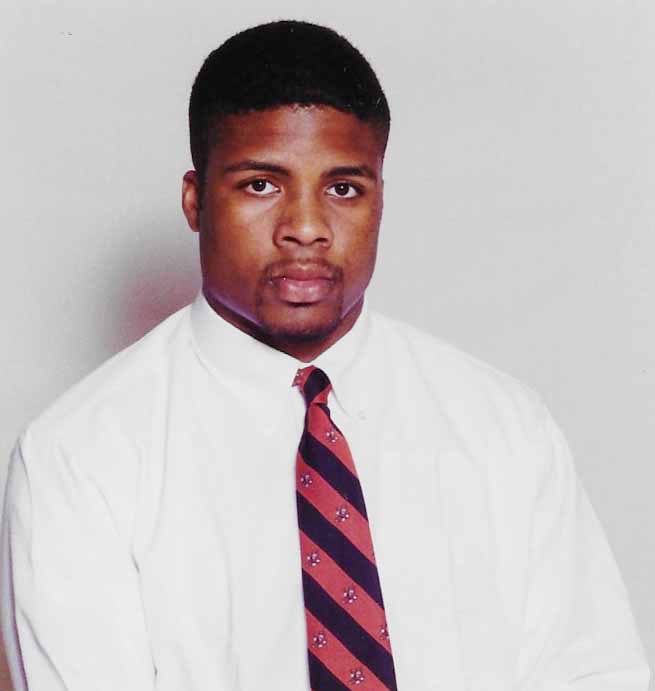

George Jr. played for Massillon in 1993-95 and became the starting quarterback during his senior year, suiting up at 6’-2”, 209 lbs. Playing under Head Coach Jack Rose, the team finished the season with a record of 7-3, with close losses to Mansfield, Miami Southridge, FL, and Canton McKinley. It was against McKinley that Whitfield had his best game of the year, when he completed 18 of 30 passes for 210 yards and two touchdowns. Down 17-7 at the half, he and his teammates nearly pulled off the upset, eventually losing 24-21. The game ended when the Tigers unfortunately fumbled at the Bulldog five yard line with less than a minute remaining. For the season, he completed 71 of 140 passes for 929 yards and 6 touchdowns. Subsequently, he was named the team’s Most Valuable Player and Honorable Mention All-Ohio.

George Jr. played for Massillon in 1993-95 and became the starting quarterback during his senior year, suiting up at 6’-2”, 209 lbs. Playing under Head Coach Jack Rose, the team finished the season with a record of 7-3, with close losses to Mansfield, Miami Southridge, FL, and Canton McKinley. It was against McKinley that Whitfield had his best game of the year, when he completed 18 of 30 passes for 210 yards and two touchdowns. Down 17-7 at the half, he and his teammates nearly pulled off the upset, eventually losing 24-21. The game ended when the Tigers unfortunately fumbled at the Bulldog five yard line with less than a minute remaining. For the season, he completed 71 of 140 passes for 929 yards and 6 touchdowns. Subsequently, he was named the team’s Most Valuable Player and Honorable Mention All-Ohio.

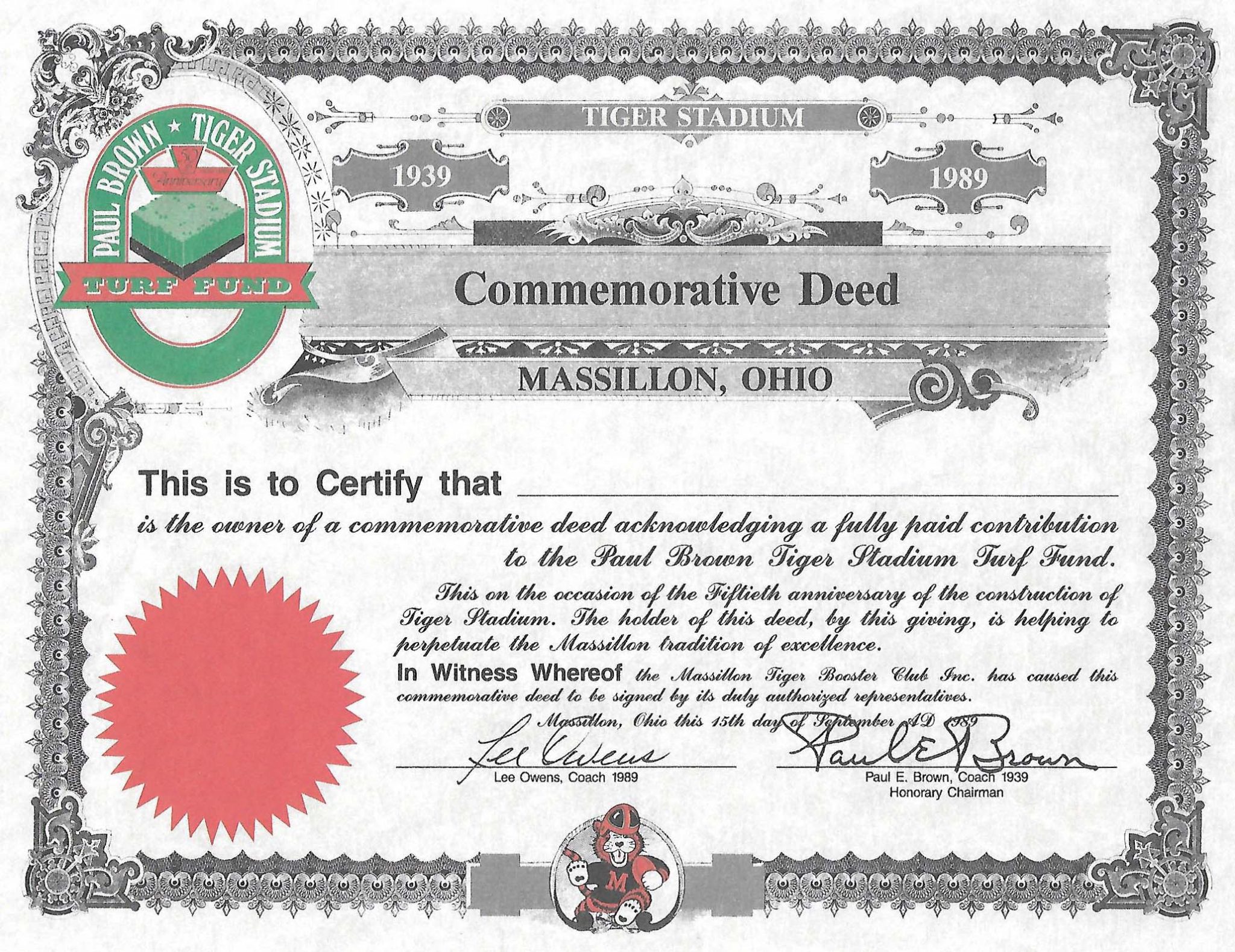

In 1938, construction of the present football facility got underway. It came about as a result of the demand for tickets on account of the success that Paul Brown achieved as he developed his storied program. The stadium was partially funded by the federal government’s Works Project Administration (WPA), which was designed to create meaningful jobs during the depression era of the 1930s at a total cost of $246,000. Originally named “Tiger Stadium,” it was renamed in 1976 as “Paul Brown Tiger Stadium” in honor of Brown, who later coached Ohio State and the professional Cleveland Browns and Cincinnati Bengals.

In 1938, construction of the present football facility got underway. It came about as a result of the demand for tickets on account of the success that Paul Brown achieved as he developed his storied program. The stadium was partially funded by the federal government’s Works Project Administration (WPA), which was designed to create meaningful jobs during the depression era of the 1930s at a total cost of $246,000. Originally named “Tiger Stadium,” it was renamed in 1976 as “Paul Brown Tiger Stadium” in honor of Brown, who later coached Ohio State and the professional Cleveland Browns and Cincinnati Bengals.