The Changing Landscape of Massillon Football – Part 1: Offensive Formations

Keith Jarvis and Bill Porrini contributed to this story

This is the first of a 7-part series, which includes the following installments:

- Part 1: Offensive Formations

- Part 2: Defensive Formations

- Part 3: Passing Frequency

- Part 4: Scheduling

- Part 5: Roster Size

- Part 6: Stadiums

- Part 7: Game Attendance

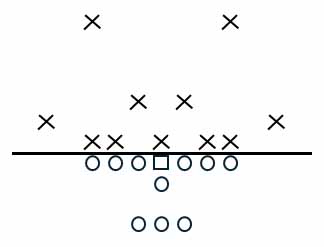

Little is known about the styles of offense used by Massillon football coaches prior to the time of Paul Brown, other than the coaches may have adopted what was being used at the time by various colleges. Massillon fielded its first team in 1891 and they most likely used mass formations, which at that time was totally within the rules, with any number of players on the line of scrimmage. They probably also used the V-formation on both kicks and scrimmage plays, the latter being referred to as the “shoving wedge.” And they certainly did not throw a pass, since it was not permitted at that time. Below is an example of a mass formation.

But in 1984 a refinement of rules was introduced in an attempt to make the game safer, certainly impacting the game’s evolution. Mass formation plays were eliminated. No more than five players were permitted in the backfield. And players could not be moving forward prior to the snap.

In 1904 a rule was put in place in that six players were required on the line at all times. In addition, the quarterback was now permitted to run, but must move laterally for at least five yards before turning up field. This led to the checkerboard-like field lines.

Continuing to emphasize safety, the college rules committee introduced the pass in 1906, although with several limitations involved, including restrictions on where the ball could be thrown, a 15-yard penalty for an incomplete pass and a loss of possession if the pass went untouched by either team. As a result, few coaches took advantage of this new rule, unless desperate enough toward the end of the game. Three years later, realizing that the change had little impact on safety since it in effect wasn’t being used, the committee removed the penalties. Little did they realize how much the game would change in the years to come.

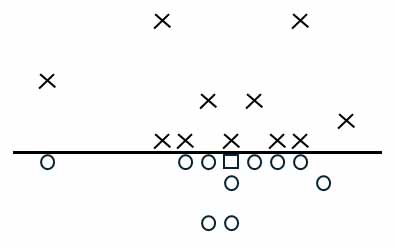

The Single-Wing Formation

A rule was added around 1907 that all players in the backfield that have the potential to receive the snap must position themselves off the line, meaning that the quarterback could not be under center. That led to the creation by Glen Pop Warner of the single-wing formation, which positioned three players in the immediate backfield and a fourth placed as a wing on the edge. The play started with a snap of the ball to any of two players position in the immediate vicinity of the center and the quarterback near the line but not able to receive the snap. In the play itself several pulling lineman would lead interference for the runner. Thus, the plays were designed to trick the defense rather than overpower it. Paul Brown (1932-40) utilized this offense to great success, while adding a pre-snap shift to introduce further confusion for the defense. His 1940 game against Canton McKinley, in which both teams used this offense, can be viewed at this link. Brown ended his career at Massillon with an 80-8-2 record, six state titles and four national titles.

It is likely that the coaches from 1907 up to Paul Brown also used this offense. It is also likely that Massillon’s next three coaches, Elwood Kammer (1942-44), Augie Morningstar (1945), Bud Houghton (1941, 46-47) used the single-wing.

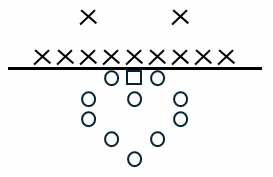

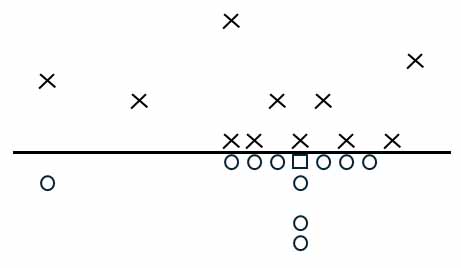

Full House T-Formation

In 1945 the rule requiring backfield players to be positioned several yards behind the line of scrimmage was removed, opening the door to the T-Formation. This concept was created by Walter Camp in 1882 as a form of “mass formation” play, designed to provide a faster-paced, higher-scoring game. The basic concept was a quarterback under center, a fullback behind the quarterback and a halfback on either side of the fullback. But the T-Formation was placed on the shelf for a while, in favor of the single-wing, prior to when the aforementioned rule change went into effect.

New Massillon Coach Mather (1948-53) introduced the T to Massillon football, with an oft-used modification that involved repositioning one of the halfbacks on the wing to gain an additional advantage on the defense. The Tigers enjoyed great success with this new offense, winning 57 of 60 games and capturing six state and three national championships. Mather’s 1953 game against Canton McKinley can be viewed at this link. Interestingly, the Bulldogs, who went through two coaching changes during the time of Chuck Mather, were still running the single-wing, which makes one believe that use of the T-formation was unique to Mather and a step ahead of the competition. After Mather left for Kansas, Tom Harp (1954-55) was hired and he also used the T-Formation.

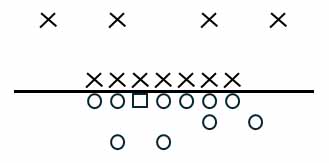

Wing-T Formation

The T-Formation was designed as a power football concept. But not all high school teams had the player size required to be effective with it. So, many opted for the Wing-T. It was created by David M. Nelson, coach of Maine (1949-1950) and later coach of Delaware, as an offshoot of the single-wing. It utilized motion and misdirection in the run game along with short passes. With a quarterback under center, a fullback was positioned directly behind and a halfback next to the fullback. The fourth back was on the wing. Often, the wingback would motion before the play began.

Several Massillon coaches in succession used the Wing-T, including Lee Tressel (1956-57), Leo Strang (1958-63), Earl Bruce (1964-65), Bob Seaman (1966-68) and Bob Commings (1969-73). Strang also modified the formation by using an unbalanced line (moving a tackle to the other side of the center). Strang, Bruce and Commings each won state titles with it.

Power-I Formation

Massillon returned to power football at times, but with the Power-I. This formation was developed by Tom Nugent, coach of VMI in 1950 as a replacement for the single-wing and an alternative to the T-formation. The quarterback was under center and immediately behind him was a fullback in a 3-point stance. Standing upright behind the fullback was a tailback, who was normally featured in the run game. It provided a good ground attack providing the tailback was sufficiently talented, but was somewhat restricted in the passing game.

Chuck Shuff (1974-75), John Moronto (1985-87) and Jack Rose (1992-97) each utilized the Power-I as coaches at Massillon, but combined to qualify for the playoffs only three times in eleven tries.

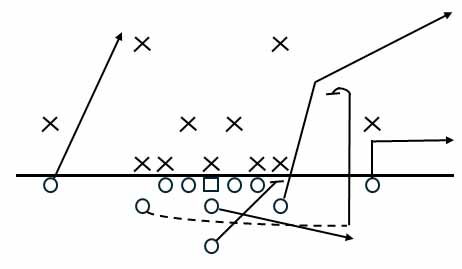

Run-and-Shoot Formation

Major changes were in store at Massillon when Mike Currence (1976-84) brought his run-and-shoot offense to town. According to him, football was going to be fun again and there was now a place for the smaller player. The players responded and Currence had around 90 juniors and seniors on each of his nine rosters.

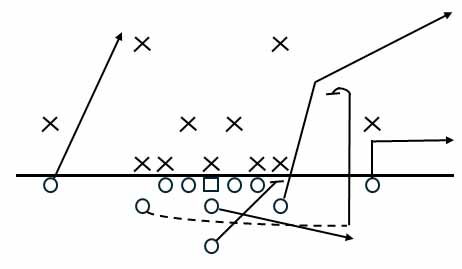

The original run-and-shoot offense was created by Glenn “Tiger” Elllison as a ploy to make average teams more competitive. Currence readily embraced it, while simplifying it for use at the high school level. His base formation involved five interior linemen with a split end on either side. The quarterback was under center with a fullback behind in a 3-point stance. Finally, a wingback was positioned off of each tackle. The play began with one of the wingbacks going in motion. Running plays resembled that of the Wing-T offense, while pass plays were more like a pre-cursor to the spread offense when there are three receivers on one side of the ball. After the motioning wingback cleared the interior line, the QB would roll to the direction of the motion, seeking one of three potential targets on one side of the field: the wide receiver and both wingbacks. Of course, there was also the option for the QB to tuck the ball and run.

With a formation that had five offensive lineman, the defensive end was uncovered, freeing him to pressure the quarterback. The blocking assignment therefore went to the fullback, who led interference for the quarterback. The fullback was taught to take out the defensive end by blocking low. But the OHSAA introduced a new rule requiring the fullback to stay on his feet for the block. So, unless the fullback weighed well in excess of 200 pounds, he was at a decided disadvantage against the larger defender. As a result (and this was at the time of Chris Spielman), Currence went more to an I-formation with pocket passing. So, the pass part of Currence’s run-and-shoot was short-lived.

Currence qualified for the playoffs three times during his eight years and twice advanced to the Division 1 state finals.

Run-and-Boot Formation

It was called the “run-and-boot,” introduced by new head coach Lee Owens (1988-91). Multiple formations; quarterback under center; one or two running backs; one or two tight ends; two wide receivers; and some quarterback option rollouts. Basically, the offense was adapted to the available personnel. But you won’t find it in the literature. It was all Owens’. He enjoyed good success during his four years, qualifying for the playoffs three times in four years.

Spread Formation

Rick Shepas (1988-04) brought the spread to Massillon and it has continued to this day with the likes of Tom Stacy (2005-07), Jason Hall (2008-14) and Nate Moore (2015-23). Created by high school coach Jack Neumeier in 1970, his modern version was designed to create mismatches and isolations in the passing game. But it requires a good passing quarterback to be successful. No longer do defenses rule the day. Call it the “great equalizer” for teams that use it when lacking size on the line.

The spread has been used by the Tigers continuously over the past 26 years, producing 17 playoff qualifications, ten regional championships, five state finals appearances and one state title.

Performance Review

Formations changed throughout Massillon’s long history for several reasons. Some developed as a result of modifications to the rules, enacted in an attempt to make the game safer. Others were used to better fit the talent-level of the players. Many coaches simply followed the current trends. But the ultimate goal was to gain a perceived advantage in the ability to score points and thereby win more games. But in reality, changing formations did not always produce the desired results. At least not until the spread offense came into play.

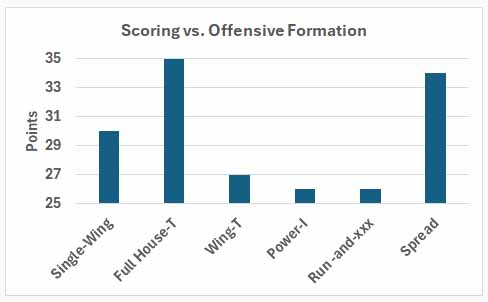

The chart below shows Massillon’s average offensive scoring for each formation. The data indicate that the single-wing, the T-formation and the spread produced the best scoring results, averaging 30-36 points per game. Meanwhile, the other offenses averaged 26-27. But one should consider that the results of the single-wing were highly influenced by the coaching of Paul Brown. Subsequent coaches averaged much less. In addition, the results of the T-formation were highly influenced by the coaching of Chuck Mather. Tom Harp, who followed Mather, also averaged much less. Only the spread has shown consistent improvement in scoring, with each of the four coaches that used it producing similar, but ever improving, results.

So, it can be reasonably concluded that the spread formation is the best offense, while the other formations, although considered progressive at the time, produced relatively the same lesser results. In other words, attempts to improve on scoring by changing formation were meager at best, and only improved when it was more influenced by the talent levels of the coaches rather than the formations themselves. Except for the spread offense.