The Common Thread that Unites Ohio’s Football Dynasties

Throughout the history of Ohio high school football there have always been a select few teams that dominated the scene. Many have had noteworthy periods of year-to-year success that sports fans like to refer to as “dynasties.” Several good teams, like Massillon, Cincinnati Moeller and Cleveland St. Ignatius for example, have withstood the test of time and still dominate today, while the dynasties of many others have come and gone.

And it’s no secret that the one trait these dynastic schools have in common is long-term, highly successful head coaches. The most notable of these are Massillon’s Paul Brown, Moeller’s Gerry Faust and St. Ignatius’ Chuck Kyle. But there was also Cincinnati Colerain’s Kerry Coomb, Canton McKinley’s Bup Rearick and Upper Arlington’s Marvin Morehead. Plus many others.

This story presents what is judged to be the best dynasties since the beginning of scholastic football in Ohio, covering a span of some 130+ years. Also included is some background on each of the teams’ successful head coaches.

First off, a little clarification regarding the definition of the word “dynasty.” A dynasty is considered to have been achieved when a school develops sustained success over a significant period of time; for this story it is a minimum of ten years, with an unbroken string of season records of 7-3 or better, while at times including the rare outlier. There must have been dominance over most competitors. The school must have brought something unique to the game that produced this success. And finally, after the dynasty ends, it is documented in the history books and/or recalled by most football fans through common knowledge.

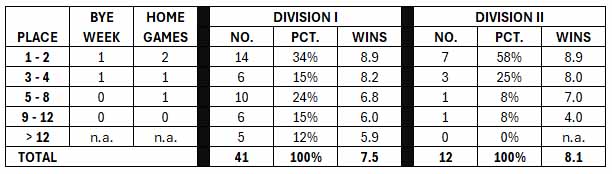

The list of dynasties shown below, ranked by duration, includes solely Division I and Division II schools. With all due respect to the highly successful smaller schools, they aren’t necessarily playing the top competition in the state. The exception is Division III Toledo Central Catholic, which plays mostly DI and DII schools.

Massillon – 33 years, from 1933 to 1965 (191-30-2; .861). The winning tradition at Massillon has endured for nearly a hundred years. But it really took off with the hiring of head coach Paul Brown in 1932. Throughout his eight years at Massillon, he compiled a record of 80-8-2, winning six state championships and three national championships. After leaving Massillon he went on to coach Ohio State, the Cleveland Browns and the Cincinnati Bengals. Brown put a remarkably successful program together that has endured to this date. While many coaches have the talent to win a vast majority of their games, often the successful performances diminished once they departed. But the City of Massillon committed itself to retaining what Brown had built. As a result, the consistent success of the Tigers has remained ever since, attesting to this endeavor. Concurrent with that, a string of subsequent successful coaches was also a key to maintaining the program. Two of these were Chuck Mather and Leo Strang. Mather (1948-53) won 57 of 60 games and captured the sportswriters’ state title each year, in addition to three national championships. Strang (1958- 63) also came up big, with a record of 54-8-1, including two state championships and three national championships. The dynasty concluded with back-to-back unbeaten seasons by future Ohio State head coach Earl Bruce.

Massillon also enjoyed three other noteworthy periods. Bob Commings (1969-73) had a 5-year record of 43-6-2, with a state championship in 1970 and a spot in Ohio’s first ever state playoffs game in 1972. He left to become the head coach of the University of Iowa. Mike Currence (1976-84) had a fine 8-year run from 1976 to 1983, compiling a record of 80-15-2, with two state finals appearances. And current head coach Nate Moore (2015-24) has a record of 110-25, with a Division II state championship in 2023, six regional championships and five state finals appearances.

Cincinnati Colerain – 30 years, from 1991 to 2020 (285-33; .843). Colerain had two coaches during this period: Kerry Coombs (1991-2006) and Tom Bolden (2007-18). Coombs had instant success with his program and compiled a record of 161-34, with a state title in 2004, along with five regional titles. Subsequently, he coached at the University of Cincinnati, Ohio State and with the Tennessee Titans. Bolden took over in 2007 and produced a fine record of 132-21. During his time there the Cardinals captured three regional titles and reached the state finals once. He left in 2018 to become the head of coach of Lakota West.

Cincinnati Moeller – 21 years, from 1970 to 1990 (217-24; .900). It took a while for inaugural Crusader coach Gerry Faust (1962-1980) to get it going, but once he did there was success after success. Moeller’s record during his time there was 178-23-2 and during the dynasty he captured five state championships, seven regional championships and four national championships. Faust left to become the head coach of Notre Dame and then the head coach at the University of Akron. In 1982 Steve Klonne (1982-2000) became the head coach and during his 19 years he had a record of 169-48. He won two state titles and three regional titles, plus a national title in 1982.

Pickerington Central – 19 years, from 2006-24 (191-40; .827). In 2003 Pickerington High School split into North and Central and Jay Sharett (2003-22) was hired to become Central’s first coach. Once the program matured his squad became one of the most dominant teams in Ohio, something that has continued to this day. He retired after last season with a record of 211-42, including two state titles, eight regional titles and two state runners-up. In fact, Central captured the regional title each year from 2016 to 2020.

Canton McKinley – 18 years, from 1933 to 1950 (148-25-10; .836). Three different coaches were the major contributors at this time, including Jimmy Aiken (1932-35), John Reed (1936-40) and Bup Rearick (1942-49). Aiken compiled a record of 34-7-1 and won a state title in 1934. He went on to coach at Akron, Nevada and Oregon. Reed succeeded Aiken and had a record of 39-7-2 over five years, but was stymied by Paul Brown’s Massillon teams, which wiped out four potential unbeaten seasons. Rearick produced a record of 67-8-4, with state championships in 1942 and 1949. He was also a long-time McKinley basketball coach.

14 years, from 1968-81 (125-25-3; .827). Again, three different coaches contributed to the run, including Ron Chismar (1965-69), John Brideweser (1970-79) and Terry Forbes (1980-81). Chismar coached for five years and was 37-13. Five years later he was the head coach of Wichita State. Brideweser coached for ten years, all within the dynasty, and was 77-21-3. Finally, Forbes coached for the last two, with a record of 22-2. His 1981 team went 13-0 and captured the Division I state title. Later, Forbes was an assistant coach for both the University of Akron and Notre Dame University.

The Bulldogs also had a good 7-year run, from 1992 to 1998, with all except one year under head coach Thom McDaniels, who had an overall record there of 131-41. During the run, the Bulldogs captured three regional titles and a state title, in 1997. They also won the national title that year. Kerry Hodakievic coached the final year of the 7-year run and also had a state title.

Lakewood St. Edward – 17 years, from 1970 to 1986 (140-35-3; .795). The Eagles were highly successful in the ‘70s and ‘80s, mostly under head coach Dan Flaherty (61-23-2), who accounted for approximately half of the seasons. Other contributing coaches included Fred Orr, Denny Martin, Mike Currence and A. O’Neil. St. Eds won three regional crowns during that time.

14 years, from 2010 to 2023 (161-25; .866). This dynasty was led by two coaches: Rick Finotti (62-15) for the first five years and current coach Tom Lombardo (103-22) for the next nine. During that time, the Eagles captured eight regional titles and seven state titles. Finotti went on to become an assistant coach at Michigan and head coach at John Carroll.

Cleveland St. Ignatius – 15 years, from 1988-2002 (157-17; .902). In 1988 St. Ignatius supplanted Cincinnati Moeller as the dominant team in Ohio. And they went on to put together a string of fifteen very successful campaigns, all under head coach Chuck Kyle (1983-23). Recently retired, Kyle’s teams went 379-117-1 during his career. Throughout the stretch, Ignatius won twelve regional championships and nine state championships. The school was also named national champion in 1989, 1993 and 1995.

Avon – 15 years, from 2010 to 2024 (178-22; .890). Avon owes their success to long-time and current coach Mike Elder (2001-24). He has compiled a career record there of 232-52 and accounts for all fifteen years of the dynasty. Eight times Avon has won the regional title, including seven times in the last eight years. Finally, in 2024, the Eagle were able to take home the Division II state championship.

Hilliard Davidson – 13 years, from 2004 to 2016 (132-24; .846). Head coach Brian White (199-58) spent 17 years at Davidson, from 1999 to 2016. Under his leadership, the Wildcats were a dominating force in the Columbus area for a 13-year period of time. Five times they captured the regional championship and twice were the state champions (2006 and 2009).

Toledo Central Catholic – 13 years, from 2012 to 2024 (177-25-2; .873). Greg Dempsy (1000-24) has been the head coach of the Irish for the last 25 years, with an overall record of 266-55. He has had an ongoing dynasty for the last thirteen, during which Central has won six regional titles and two state titles in Division III and three regional titles and two state titles in Division II.

Centerville – 12 years, from 1976 to 1986 (112-11; .911). Bob Gregg coached at Centerville for 28 years, compiling a record of 219-62. He had his best run from 1976 to 1986 during which time the Elks claimed a Division I regional title, in 1984. Later, Gregg was the coach in 1991 when Centerville competed in the state finals.

Upper Arlington – 11 years, from 1964 to 1974 (99-9-2; .909). The Golden Bears burst onto the scene in 1966 when they scored a 21-6 victory over 2-time defending state champion Massillon. The following year they also turned the trick with a 7-6 win, this time achieving a state title, a crown they again won in both 1968 and 1969. Two coaches contributed to the 11-year run: Marvin Moorehead and Pete Corey. Moorehead coached from 1955 to 1969, compiling a 57-1 record during the streak. Cory took over from Moorehead and coached through 1986, with a record of 42-8-2 during the streak. Although Corey left at that time, he returned from 1986 through 2021 as offensive coordinator.

Akron Hoban – 10 years, from 2015 to 2024 (129-16; .890). Current coach Tim Tyrell assumed the reigns of Hoban in 2016 and has been the primary contributor to the dynasty, with an overall record of 118-12. During the 10-year span the Knights captured two state titles in Division III, along with seven regional titles and three state titles in Division II.

Huber Heights Wayne – 10 years, from 1981 to 1990 (85-17-3; .824). Mike Schneider was the head coach for Wayne for 17 years, from 1981 to 1997, compiling a record of 128-43-3. His dynasty spanned 1981 through 1990.

The Tigers were coming off of a very successful 1989 campaign in which they recorded a win over Canton McKinley followed by playoff regional championship. The 1990 season promised more of the same beginning with wins over Stow (8-2) and Covington Catholic (9-1), along with a 1-point loss to Cincinnati Moeller. But a 14-7 setback to Austintown Fitch (8-2) showed that there were kinks in the armor. And those kinks were ever so present in one-sided losses to McKinley and Sandusky at the end of the season. On the plus side, Massillon would return several promising junior players for the next season.

The Tigers were coming off of a very successful 1989 campaign in which they recorded a win over Canton McKinley followed by playoff regional championship. The 1990 season promised more of the same beginning with wins over Stow (8-2) and Covington Catholic (9-1), along with a 1-point loss to Cincinnati Moeller. But a 14-7 setback to Austintown Fitch (8-2) showed that there were kinks in the armor. And those kinks were ever so present in one-sided losses to McKinley and Sandusky at the end of the season. On the plus side, Massillon would return several promising junior players for the next season.

Single season solo tackles, total tackles and tackle points – In 1982 Spielman in 13 games recorded 113 solo tackles and 43 assists, totaling 156 total tackles and 5 tackle points. He also had four pass interceptions and recovered two fumbles. Following the season he was named 1st Team All-Ohio at linebacker. The Tigers finished the year with a 12-1 record and advanced in the playoffs to the Division I state finals. Although Spielman wasn’t the fastest player on the field, his ability to read the play prior to the snap based on the opponent’s formation and also anticipate of the flow of the play when it began was perhaps unmatched by any previous Massillon player.

Single season solo tackles, total tackles and tackle points – In 1982 Spielman in 13 games recorded 113 solo tackles and 43 assists, totaling 156 total tackles and 5 tackle points. He also had four pass interceptions and recovered two fumbles. Following the season he was named 1st Team All-Ohio at linebacker. The Tigers finished the year with a 12-1 record and advanced in the playoffs to the Division I state finals. Although Spielman wasn’t the fastest player on the field, his ability to read the play prior to the snap based on the opponent’s formation and also anticipate of the flow of the play when it began was perhaps unmatched by any previous Massillon player.

Single season pass interceptions – In 2002 Relford intercepted 12 passes to set the single-season record. Four of the picks came against North Canton Hoover during a 31-0 playoff game victory. Included in that was returned 50-yard return for a score. He also ran back an interception 80 yards for TD against Cleveland St. Ignatius. The Tigers finished 12-3 that year and advanced in the playoffs to the Division I state semifinals.

Single season pass interceptions – In 2002 Relford intercepted 12 passes to set the single-season record. Four of the picks came against North Canton Hoover during a 31-0 playoff game victory. Included in that was returned 50-yard return for a score. He also ran back an interception 80 yards for TD against Cleveland St. Ignatius. The Tigers finished 12-3 that year and advanced in the playoffs to the Division I state semifinals. Career assisted tackles and total tackles – During his 3-year career Leno, playing at linebacker, recorded 123 solo tackles and 173 assisted tackles, for a total of 296 tackles. He also had 21 tackles for loss. His most productive games came in 2009 against Steubenville (11 solos, 4 assists) and Cleveland St. Ignatius (6 solos, 7 assists). Following the 2009 10-4 season Leno was named Special Mention All-Ohio.

Career assisted tackles and total tackles – During his 3-year career Leno, playing at linebacker, recorded 123 solo tackles and 173 assisted tackles, for a total of 296 tackles. He also had 21 tackles for loss. His most productive games came in 2009 against Steubenville (11 solos, 4 assists) and Cleveland St. Ignatius (6 solos, 7 assists). Following the 2009 10-4 season Leno was named Special Mention All-Ohio. Single game total tackles – In 1950 in a game against Warren Harding, Vliet recorded an unbelievable 42 tackles. Vliet’s asset was that he was incredibly adept at finding the ball carrier during the play, whether it was a running back or a receiver. So for this game, Head Coach Chuck Mather told Vliet that he wanted him to make all of the tackles. Meanwhile, the remaining ten players were instructed to prevent the Harding players from blocking Vliet. The ploy worked and the Tigers went on to win 23-6.

Single game total tackles – In 1950 in a game against Warren Harding, Vliet recorded an unbelievable 42 tackles. Vliet’s asset was that he was incredibly adept at finding the ball carrier during the play, whether it was a running back or a receiver. So for this game, Head Coach Chuck Mather told Vliet that he wanted him to make all of the tackles. Meanwhile, the remaining ten players were instructed to prevent the Harding players from blocking Vliet. The ploy worked and the Tigers went on to win 23-6. Single game quarterback sacks – In the 2005 season opener against Dover, McCall set a single-game record with 5 quarterback sacks. He also had 8 solo tackles and one assist, with 2.0 tackles for loss. Massillon won the game, 34-0. By season’s end, McCall led the team in total tackles, tackles for loss and quarterback sacks. He was also named 2nd Team All-Ohio. As a team, the Tigers finished 13-2 and advanced in the playoffs to the Division I state finals.

Single game quarterback sacks – In the 2005 season opener against Dover, McCall set a single-game record with 5 quarterback sacks. He also had 8 solo tackles and one assist, with 2.0 tackles for loss. Massillon won the game, 34-0. By season’s end, McCall led the team in total tackles, tackles for loss and quarterback sacks. He was also named 2nd Team All-Ohio. As a team, the Tigers finished 13-2 and advanced in the playoffs to the Division I state finals. Single game pass interceptions – In Game 2 of the 2005 season Massillon traveled south to face Cincinnati Elder in Paul Brown Stadium. Defensive back Troy Ellis had a career day against the Panthers by intercepting 5 passes. He also returned a fumble 25 yards for a score. Massillon led 35-7 at the end of the third quarter, but managed to hold on to win, 35-31.

Single game pass interceptions – In Game 2 of the 2005 season Massillon traveled south to face Cincinnati Elder in Paul Brown Stadium. Defensive back Troy Ellis had a career day against the Panthers by intercepting 5 passes. He also returned a fumble 25 yards for a score. Massillon led 35-7 at the end of the third quarter, but managed to hold on to win, 35-31. Single season assisted tackles – In 2018 Krichbaum recorded 78 assisted tackles in a 15-game season. He also led the team that year with 119 total tackles and 80.0 tackle points, with 10.5 tackles for loss. As a team Massillon was perfect in the win-loss column until the Division II state finals.

Single season assisted tackles – In 2018 Krichbaum recorded 78 assisted tackles in a 15-game season. He also led the team that year with 119 total tackles and 80.0 tackle points, with 10.5 tackles for loss. As a team Massillon was perfect in the win-loss column until the Division II state finals. Single season tackles for loss – In 2023 Pringle recorded 24.5 tackles for loss, while also finishing second in total tackles and quarterback sacks. His 2023 record erased the previous mark of 21.5, which he also set in 2022. His fortes were the abilities to find the ball in a crowd to make the tackle and also exhibit a ferocious pass blitz. Simply put, he was a “player,” along the lines of a Chris Spielman.

Single season tackles for loss – In 2023 Pringle recorded 24.5 tackles for loss, while also finishing second in total tackles and quarterback sacks. His 2023 record erased the previous mark of 21.5, which he also set in 2022. His fortes were the abilities to find the ball in a crowd to make the tackle and also exhibit a ferocious pass blitz. Simply put, he was a “player,” along the lines of a Chris Spielman.