Stanfield Wells – Wall of Champions

Stanfield Wells was Massillon’s first collegiate All-American, earning that distinction at the University of Michigan. But his claim to fame went well beyond that and he did something in football that very few other players had done up to that time. Here is his story.

Stanfield Wells was born on July 25, 1889, growing up in the great plains. In 1906, prior to his senior year of high school, his family moved to Massillon and he was introduced to the game of football for the first time in his young life. It came at the behest of his classmates, who needed to talk him out of his reluctance join.

“That was my senior year,” Wells recalled much later in life in a letter to Charles Gumpp, President of the Massillon Football Booster Club. “I was a ‘new boy’, having just moved to Massillon that summer from the wide open spaces of South Dakota, Wyoming and Nebraska. The first day at school several of my classmates came around to suggest that of course I was coming out for football. And although I protested that I had never had a ball in my hands, they countered with the argument that I was a good-sized lump of a boy and would make a fine prospect. So, I promised.

“That was my senior year,” Wells recalled much later in life in a letter to Charles Gumpp, President of the Massillon Football Booster Club. “I was a ‘new boy’, having just moved to Massillon that summer from the wide open spaces of South Dakota, Wyoming and Nebraska. The first day at school several of my classmates came around to suggest that of course I was coming out for football. And although I protested that I had never had a ball in my hands, they countered with the argument that I was a good-sized lump of a boy and would make a fine prospect. So, I promised.

“Well, the only preparation necessary was to take an old pair of shoes down to the town cobbler and have some cleats nailed on them. I think the athletic association must have had some football pants, but I do remember distinctly that you had to furnish your own stockings (any color) and an old sweater. Put these on and you were in business.

“I can’t believe that there were more than eleven candidates out because I made the team the first afternoon. Nor did we have a regular coach. A boy named Fritz Merwin, who I think had played the year before was our coach. If you ask me, he’s the one whose picture ought to be hanging up around there someplace. He didn’t get paid anything. And if a coach ever had an awkward squad of eleven nitwits, he did. But he was out there every afternoon, early and late, teaching us fundamentals instead of fancy razzle-dazzle plays, and in the end it paid off because we won a few games.”

Wells must have made an immediate impact on the team, because he was named team captain, playing left halfback along with his twin brother, Guy. But the season wasn’t as successful as he recalled, with the team having posted a 1-5 record, including a 21-0 win over Wooster and a pair of losses to Canton Central.

Staying with sports, he was then captain of basketball team.

A few years later he enrolled at the University of Michigan, where joined the football team as a tackle, with his 1909 team posting posting a record of 6-1. The following season the Wolverines finished 3-0-3, defeating Minnesota 6-0 to win the Western Conference championship. Wells was stellar. playing the first three games at right tackle and then moving to right end for the remainder of the season. For his effort he was named 1st Team All-American by Walter Camp.

A few years later he enrolled at the University of Michigan, where joined the football team as a tackle, with his 1909 team posting posting a record of 6-1. The following season the Wolverines finished 3-0-3, defeating Minnesota 6-0 to win the Western Conference championship. Wells was stellar. playing the first three games at right tackle and then moving to right end for the remainder of the season. For his effort he was named 1st Team All-American by Walter Camp.

But it was also when Wells put his name in the sports chronicle. Football was considered a very dangerous sport in its inaugural years due to the violence entailed with eleven offensive players constantly crashing into eleven defensive players. So dangerous was it that in 1905 there were 18 fatalities recorded, mostly among high school players. Even U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, whose son was on the freshmen team at Harvard University, took notice and was about to ban the sport if changes were not made. So, a large number of universities met to develop modifications to the rules, including banning the flying wedge on kickoffs, creating a neutral zone between the opposing linemen and increasing the first down requirement from five yards to ten.

But the greatest change was legalizing the forward pass. However, several restrictions were also added to the concept. Passes could not be thrown over the middle of the line, within five yards on either side of the center. A dropped pass resulted in a 15-yard penalty. And a pass that went untouched resulted in the offense forfeiting the ball to the defense. Obviously, the coaches steered totally away from the pass due to the penalties involved, while also believing a pass not to be a “manly” and ethical in regard to the traditional physical nature of the game. Nevertheless, the first pass was completed on September 5, 1906, by St. Louis University in a game against Carroll College. The following year Carlisle, under coach Pop Warner, used the pass as a part of its offensive package, finding great success with it. History will note that Knute Rockne was the father of the passing game, only he didn’t utilize it until 1910, three years later.

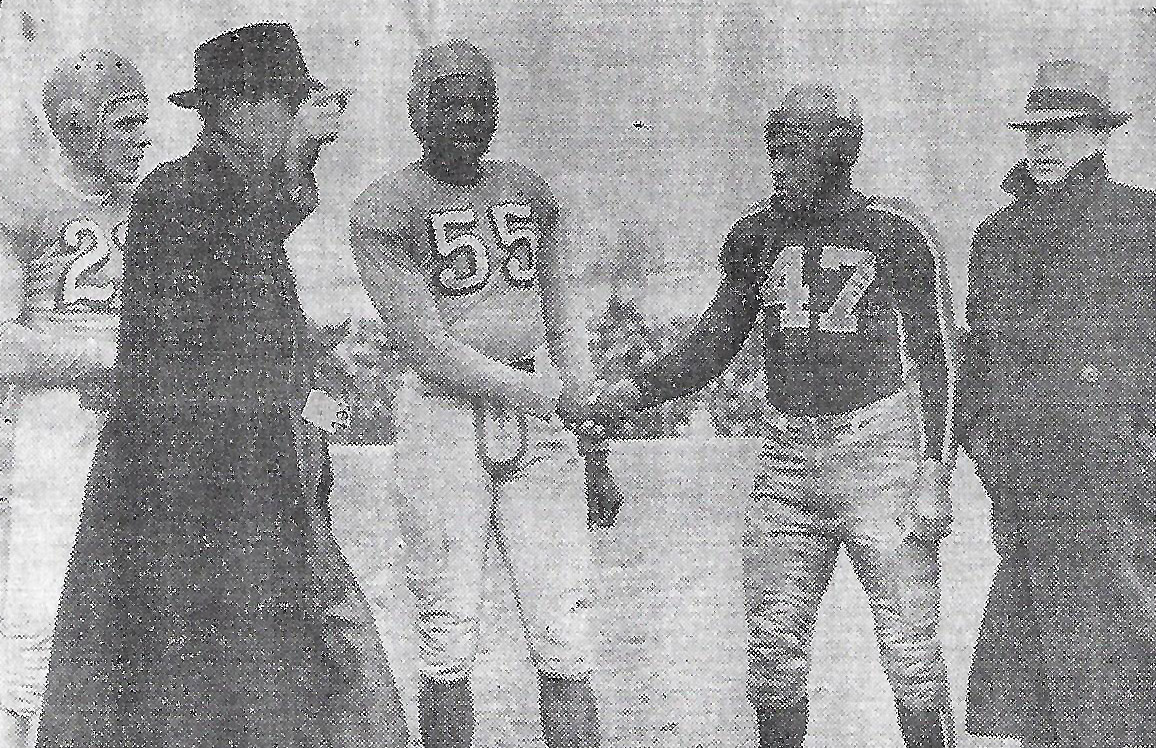

That brings us back to Wells, also in 1910. Six minutes remained in the game between Michigan and Minnesota with the two teams battling to a scoreless tie and Michigan having possession of the ball at their own 47. With the running attack stymied through, Wells dropped back and fired a pass to Sanley Borleske for a gain of 27 yards to the Gopher 30. On the next play he again connected with Borleske, who secured the pass and raced to the three yard line. Wells then carried for no gain. Finally, he managed to just breach the goal line on his second attempt for the winning score and the conference championship, scoring his only points of the season. Subsequently, the entire on-field Michigan contingent swarmed Wells and his teammates and it took several minutes before the pandemonium could be quelled and the game resumed. Wells’ effort certainly had an influence on his being named All-American. He was also named all-conference. Eventually, the penalties for an incomplete pass were removed and the aerial game was thereafter embraced by all teams at every level.

Wells completed his career at Michigan by playing right end and then right halfback, with the team finishing the season 5-1-2 and Wells scoring four touchdowns. Wells was again named 1st Team All-American, this time by both the New York Globe and Dr. Henry L. Williams. He was also awarded 3rd Team by Walter Camp. In addition, he was selected for Outing magazine’s Roll of Football Honor and 1st Team All-Western Conference.

Following college Wells played professionally for the Akron Indians, the Cleveland Indians and the Detroit Heralds, although his participation was not documented in the semi-accurate pro football archives.

Luther Emery of the Independent visited Wells while he was at Michigan and printed this: “Stanfield Wells was Massillon’s first All-American. He was a fine man, big fellow, played a little pro ball. I went up to Michigan to meet him. He was overjoyed. He got to talking and asking about some of the Massillon people he graduated with. He went back in his bedroom and came out with his Massillonian in his hand. He asked me about quite a number of ones who were in there.” (Ref. Massillon Memories, by Scott Shook).

Following football, Wells became manager of an insurance company in Nashville, Tennessee. He died on August 17, 1967, at the age of 78

In 1994 he was inducted into the Massillon Wall of Champions and in 2016 he entered the Massillon Football Hall of Fame