As a football player, Bobby Grier had a conventional career for one of the Massillon’s better players, starting for Tigers during his senior season and then playing collegiately. But in 1955 civil rights discrimination in the South reared an ugly head and Bobby, as a Black player for a Northern team, was caught in the middle. But he along with his teammates handled it admirably. And now Bobby is finally being honored by Massillon with a spot on the Wall of Champions.

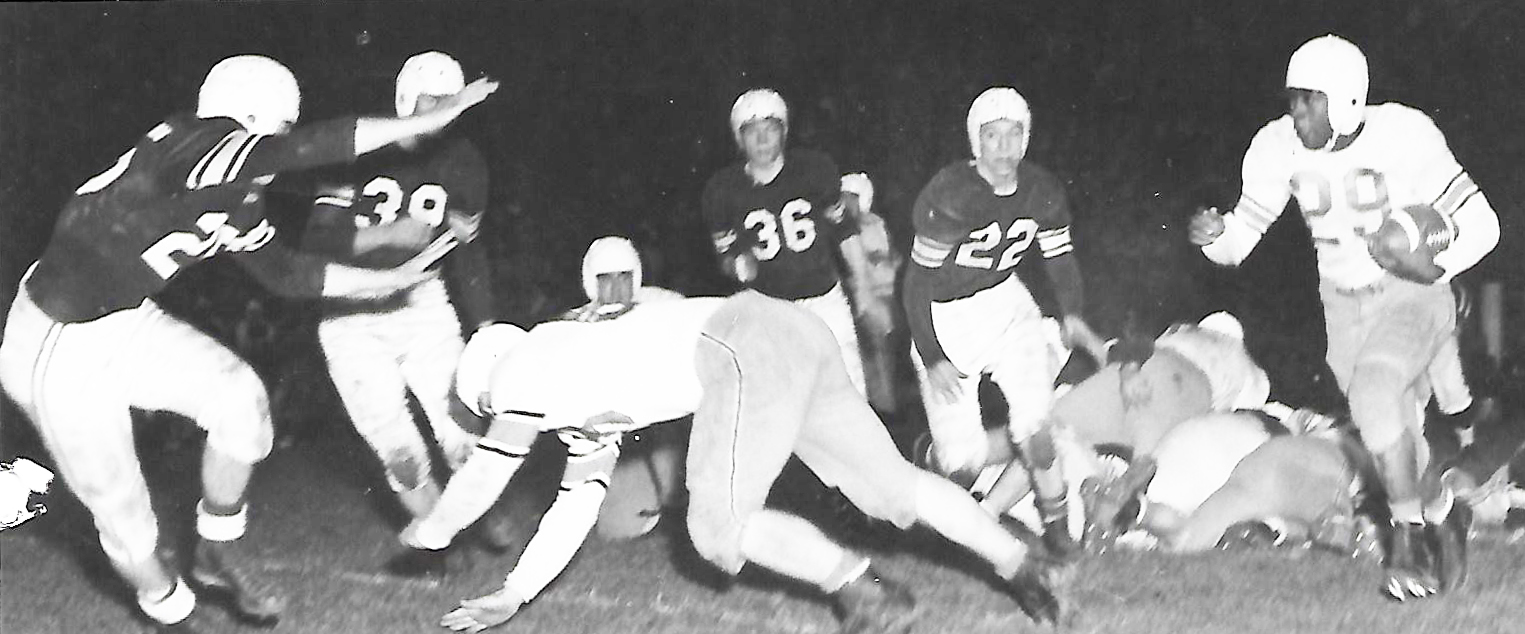

Bobby Grier suited up for the Tigers from 1949-51, playing fullback and safety under successful head coach Chuck Mather. During his junior year Massillon finished the season with a perfect 10-0 record and was named both INS state champion and national champion. The Tigers were completely dominant in all ten games, outscoring their opposition 407-37. The only team to score more than once on them was No. 8 Steubenville, which lost 35-12. In the season finale the Tigers downed No. 9 Canton McKinley 33-0. As a backup, Grier contributed five rushing touchdowns.

In 1951, the 190 lb. senior player started at halfback was instrumental in leading his team to a 9-1 record and an INS state championship, in spite of suffering a 19-13 setback to No. 7 Warren Harding. Since there were no 10-0 teams in the state of note that year and the Tigers had defeated both No. 2 Steubenville and No. 6 Barberton, plus the fact that they were defending state champs, the crown went to Massillon. Numbers-wise, they outscored their opponents 316-65.

Grier was teammates with several other outstanding players, such as Henry “Ace” Grooms, Tom Straughn, Chuck Vliet and Paul Francisco. He was also tops on the team with eleven rushing touchdowns, ahead of Grooms, who had ten, and John Francisco, who had eight. Against Steubenville he rushed 9 times for 49 yards and scored the game-winning TD. Then against Barberton he scored the only touchdown in a 6-0 victory. For his efforts he was named 2nd team All-Ohio Scholastic League and earned a Division 1 scholarship to the University of Pittsburgh.

Typical of most college players, Grier worked his way through a talented roster striving for playing time. As a sophomore he rushed 13 times for 198 yards. But his coach was not sold on his defense at a time when players were required to play both ways. Then in 1955, under Coach John Michelosen, Grier started the first game. But he shared time the rest of the season.

Typical of most college players, Grier worked his way through a talented roster striving for playing time. As a sophomore he rushed 13 times for 198 yards. But his coach was not sold on his defense at a time when players were required to play both ways. Then in 1955, under Coach John Michelosen, Grier started the first game. But he shared time the rest of the season.

Fortunately, he was a member of a very good Panther team that finished the year No. 11 in the country and was invited to participate in the 1956 Sugar Bowl in New Orleans, Louisiana. The bowl committee had their eye on West Virginia, but in the final game of the season Pittsburgh defeated the Mountaineers 27-6 and the committee elected instead to invite Pitt. Their opponent would be Georgia Tech. And it was with Tech that the problems began.

Discrimination in the South was alive and well in the 1950s and a Southern team playing in a game against Black opponent players was frowned upon. But the fact that the Black Bobby Grier was a member of the Pittsburgh team was overlooked by the bowl committee since Grier was not a starter and was not expected to play.

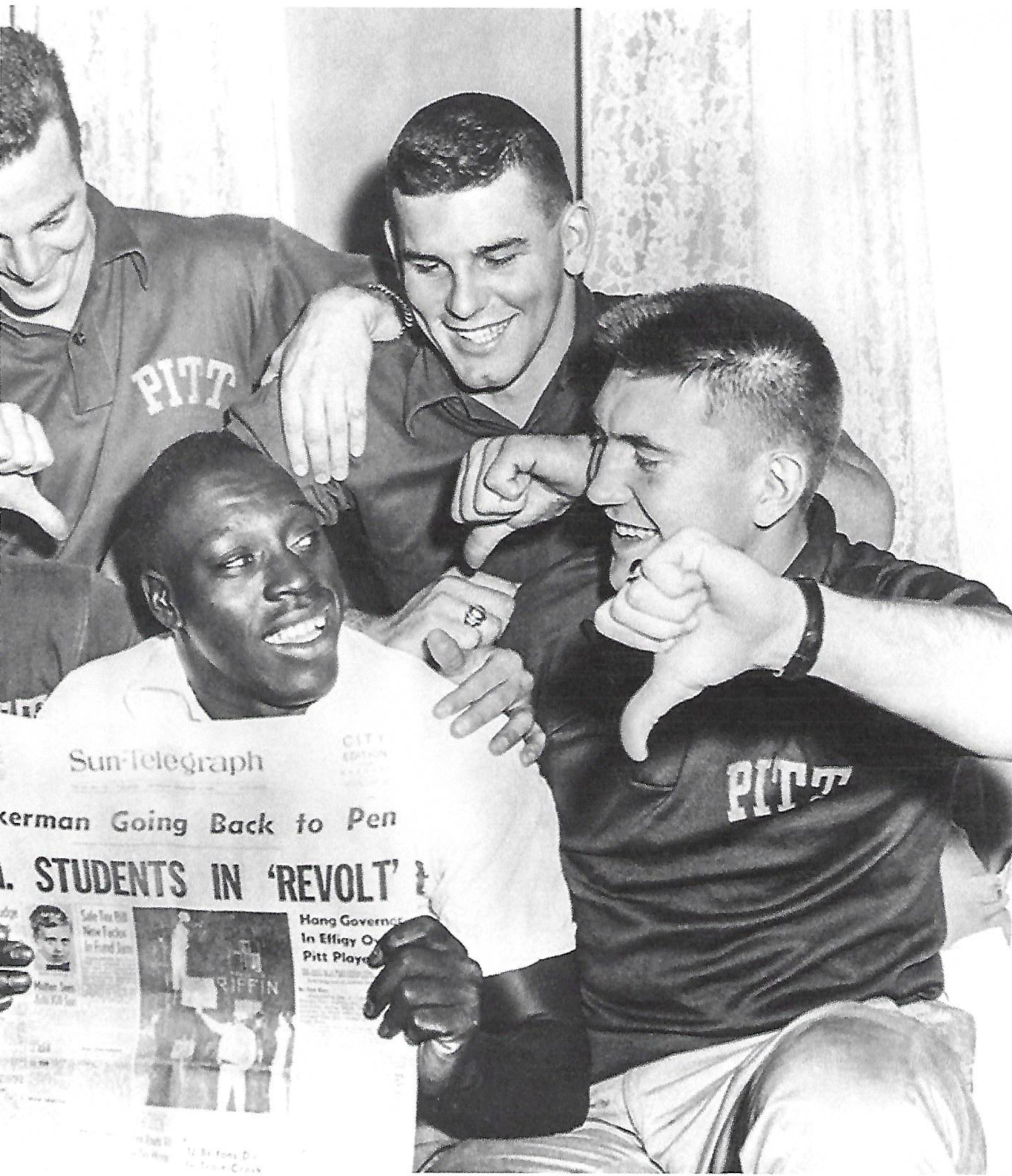

That didn’t keep Georgia Governor Marvin Griffin from urging Tech not to participate unless Grier was banned, which irked most of the country, more so than the Rosa Parks bus incident. But what Griffin didn’t expect was 2,000 Tech students rioting at the governor’s house demanding that he rescind the request, while hanging the governor “in effigy.” Even students from the University of Georgia supported Tech. The bottom line was that the Tech students wanted their team to play in the Sugar Bowl, discrimination be damned.

Back in Pittsburgh, the players voted to stay home if Grier was not permitted to play. “It made me feel great that the team, the university and everybody was behind me,” said Grier.

Back in Pittsburgh, the players voted to stay home if Grier was not permitted to play. “It made me feel great that the team, the university and everybody was behind me,” said Grier.

Eventually, the governor’s request was rejected by the Georgia State Board of Regents by a vote of 13-1. First off, the contract had already been signed and second, they really wanted Tech in the game. But still the board created a policy barring Georgia and Tech from playing integrated teams in future games, before integrated crowds, in segregated states, a ruling which seemed to appease the governor. Only the policy was never enforced.

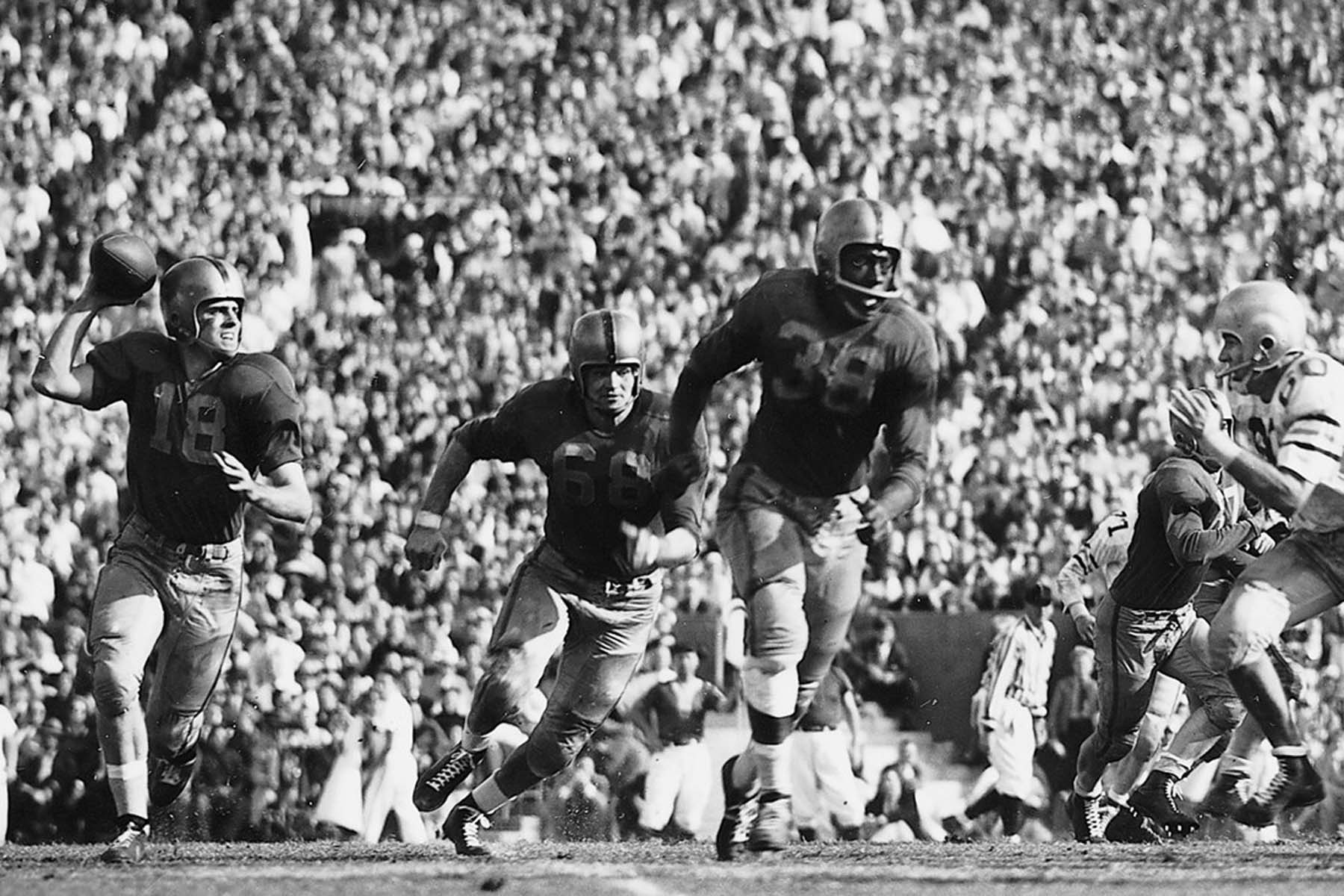

That brings us back to Bobby. As luck would have it, the Pitt starting halfback was injured during a practice prior to the game and Grier was quickly thrust into the lineup. So the game was held and everyone survived, with Blacks and Whites sitting together without incident. But in the end, Bobby Grier became the first Black player to participate in a bowl game in the South, the significance of which was not realized until many years later. Overall, the prejudice was a new experience for Grier. “In Massillon, we learned to get along with people,” he said. “We learned to play together as a team and do a good job of it. We had our differences, but we always came together in the end.”

Although Pittsburgh lost the game 7-0, Grier led all rushers with 51 yards. In an ironic twist, Grier was called for pass interference late in the game and the ball was placed at the one yard line, setting up the lone touchdown. Bobby was beside himself later in the locker room. And many thought it was Southern home cooking, noting that Grier was ahead of the receiver on the play and had been pushed to the ground prior to the ball sailing over both of their heads. But later it was determined that the referee who made the call was from Pittsburgh. After the game, following a review of the game film, the referee admitted that he simply made a mistake.

Although Pittsburgh lost the game 7-0, Grier led all rushers with 51 yards. In an ironic twist, Grier was called for pass interference late in the game and the ball was placed at the one yard line, setting up the lone touchdown. Bobby was beside himself later in the locker room. And many thought it was Southern home cooking, noting that Grier was ahead of the receiver on the play and had been pushed to the ground prior to the ball sailing over both of their heads. But later it was determined that the referee who made the call was from Pittsburgh. After the game, following a review of the game film, the referee admitted that he simply made a mistake.

No other northern team was invited to the Sugar Bowl until nine years later when Syracuse made the trip. Times were changing and the Orange featured two black players (future NFL stars Floyd Little and Jim Nance) with little fanfare.

No other northern team was invited to the Sugar Bowl until nine years later when Syracuse made the trip. Times were changing and the Orange featured two black players (future NFL stars Floyd Little and Jim Nance) with little fanfare.

After college, Grier joined the Air Force and became a missile officer. Following his service, he was an administrator at a Pittsburgh community college

In 2009 Bobby was honored as a Washington High School Distinguished Citizen. Then in in 2019 he was inducted in the Sugar Bowl Hall of Fame.

Now, in August of this year, he will be added to the Massillon Wall of Champions. Congratulations, Bobby Grier.