History

History The Changing Landscape of Massillon Football – Part 5:…

The Changing Landscape of Massillon Football – Part 5: Roster Size

Keith Jarvis, Gary Vogt, Bill Porrini and Coach Dan Studer contributed to this story.

This is the fifth of a 7-part series, which includes the following installments:

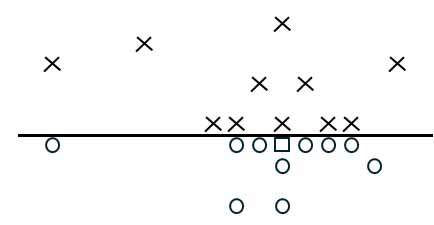

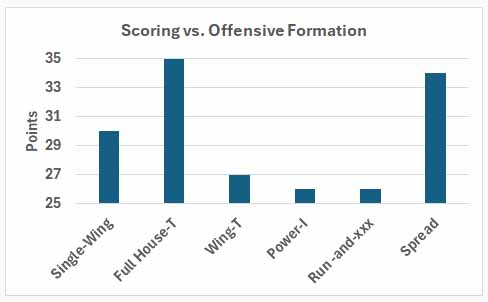

- Part 1: Offensive Formations

- Part 2: Defensive Formations

- Part 3: Passing Frequency

- Part 4: Scheduling

- Part 5: Roster Size

- Part 6: Stadiums

- Part 7: Game Attendance

Introduction

Part 5 of the series presents the evolution of Massillon’s football team roster size plus the overall school enrollment over the past 130+ years. Then, it uses the two sets of data to calculate the changes in player participation rate. Of particular interest is relationships among just the senior classes.

Varsity Roster Count

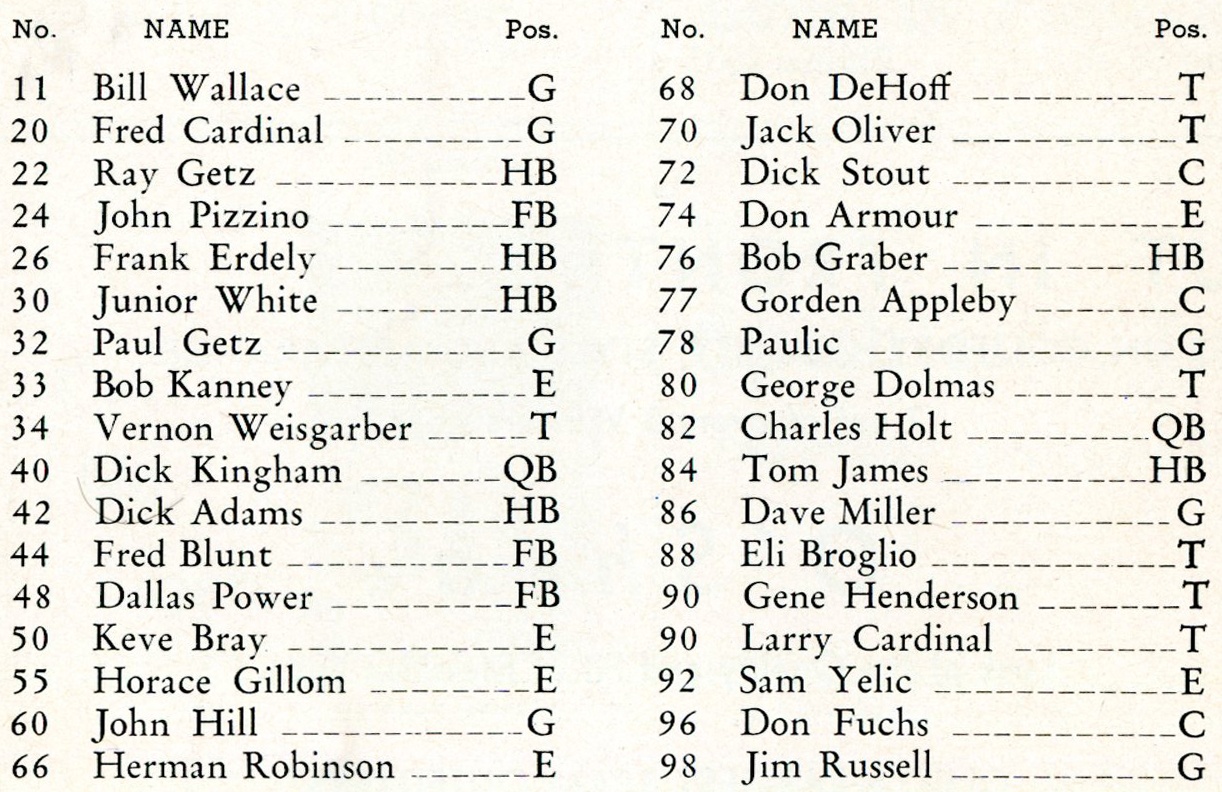

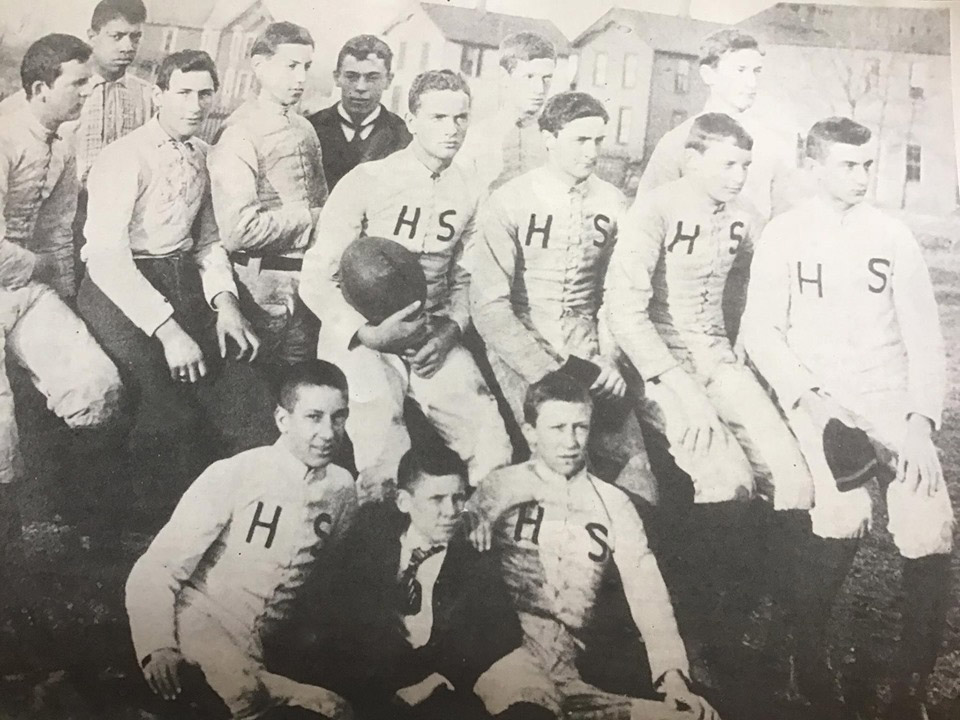

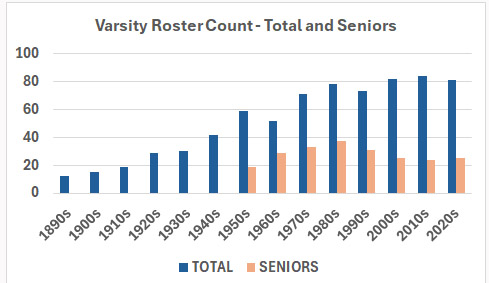

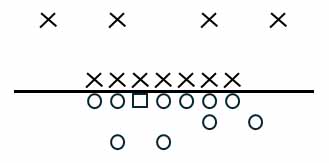

The first Massillon football team was fielded in 1891. Based on a photo from that year, it appears that the squad was very minimal, consisting of only twelve players. Since that time roster sizes have grown slowly, but to a much greater number, presently around eighty. But there were a few modifications that occurred along the way that impacted the number in both directions. Chief among those were the years during which sophomores did or did not dress on Friday night.

In the years following that 1891 team, roster sizes remained in the teens up until 1916, when Coach John Snavely enjoyed the benefit of twenty players. He also finished 10-0 that year and captured the Tigers’ second ever state title. From thereafter, roster sizes grew meagerly until Chuck Mather became the head coach. Suddenly, football was a big deal in Massillon, as reflected by the number of players. In 1948, his first year at the helm, the roster size was 65, a 30-player increase from the previous year. In fact, his six teams varied little from that number. Of course, Mather compiled a record of 57-3 and captured the state title each year.

During the four years after Mather left, the total number of varsity players remained at the larger value. But then came Leo Strang in 1958. He removed the sophomores from Friday night games and the average number dipped to 43. However, his senior classes did grow on average, from 20 to 26.

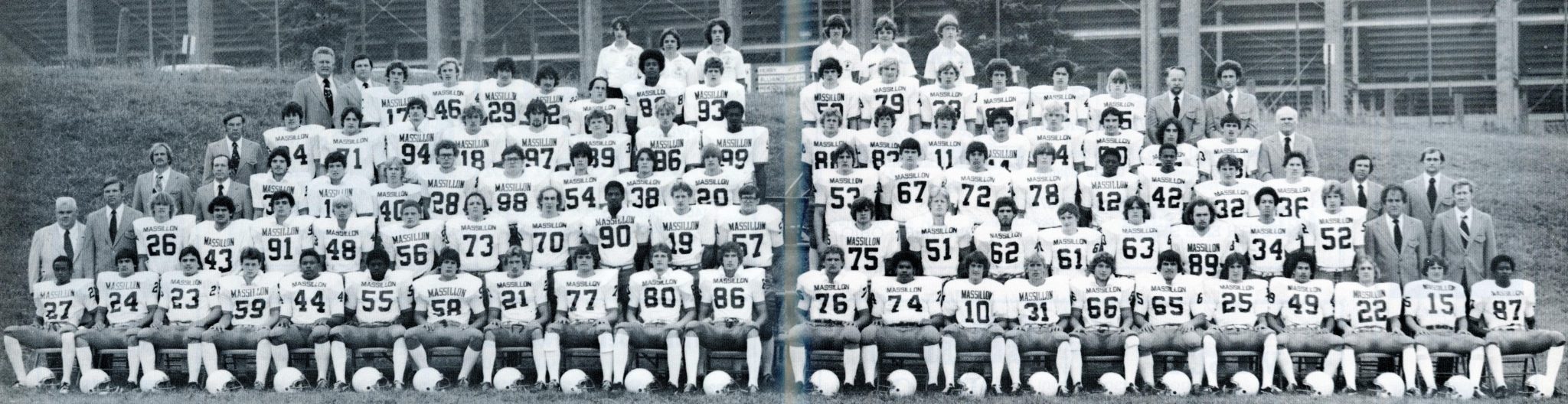

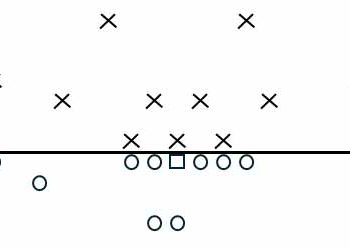

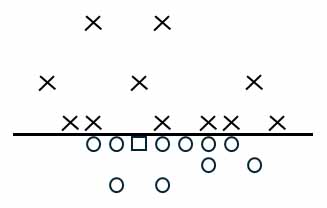

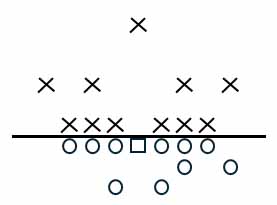

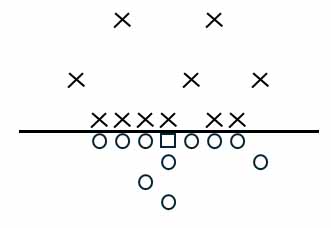

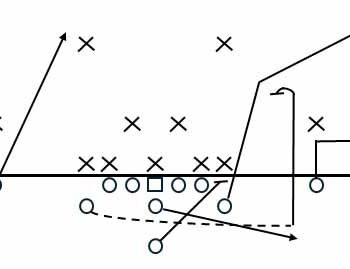

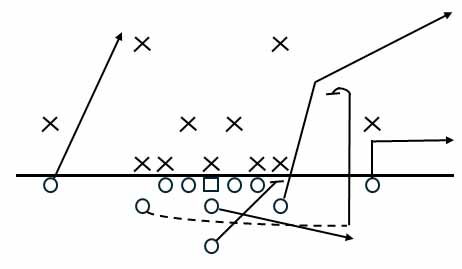

The next big jump came at the time of Coach Mike Currence, who came to Massillon in 1976. With his wide-open run-and-shoot offense, he told the boys in the school that football was going to be fun again and there was now a place for a player who had a smaller frame. So, the boys responded, increasing the sizes of the rosters to as high as 92 players, with just juniors and seniors on varsity. In fact, his 1979 team, which finished unbeaten during the regular season, fielded the largest-ever senior class: 47 players on an 88-man roster. Currence also used a 2-platoon starting lineup in order to promote specialization within positions and thereby enhance performance. This necessarily required a larger roster. The coach stayed in Massillon for nine years and was very successful, producing an overall record of 79-16-2 and participating in two Division 1 state playoff finals.

1979 Varsity Football Team

In 1999 Coach Rick Shepas was hired as coach. Experiencing a decline in school enrollment, Shepas reinstated the sophomores to the varsity squads. But he also discouraged marginal players from participating, believing them to be distractions. Nevertheless, his roster counts averaged around 75.

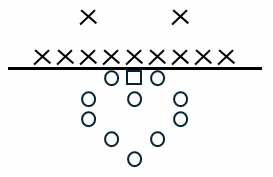

At present, with current head coach Nate Moore at the helm, sophomores have remained on the varsity roster and team sizes are in the 80s. Like Currence, he also promote a 2-platoon starting lineup. And that concept even stretches into special teams. Moore, given the success he has brought to the Tiger program, has also been the beneficiary of several high-caliber players who have relocated to Massillon in order to enhance their skills with top-quality coaches and prepare for football at the next level.

The chart below shows the progression of the roster count over time by decade. The blue bars represent all of the varsity players (total), whereas the orange bars represent only the seniors. As expected, the “total” data displays a steady progression from the early days to the present. But a different story is apparent with the seniors. Their count increased through the 1980s, but then steadily declined by about a third into the 2000s. This was certainly a reflection of the declining enrollment Massillon experienced, starting in the 1970s. Fortunately, the number of seniors has remained relatively constant over the past thirty years. Keep in mind when viewing the chart that sophomores were removed in 1958 (note the decline in the 1960s) and then reinstated in 1998.

School Enrollment

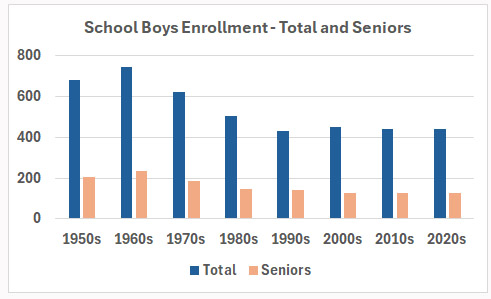

The second presentation of this story involves school enrollment, specifically the changing number of boys in grades 10 through 12. It also includes the values for just the seniors. The data gathered for this segment is shown in the chart below and is averaged by decade. The chart shows that the total enrollment (blue bars) peaked in the 1960s and then rapidly declined by 29% until the 1990s, after which it steadied out. The school’s senior enrollment (orange bars) also saw a related drop, but of a much higher amount, of 45%.

It was also after the enrollment drop that the Massillon sports administration began to shy away from scheduling the larger parochial schools. Concurrently, in 2013, following restructuring of the OHSAA playoff divisions, and on account of the decreased enrollment, the Tigers were reassigned from Division 1 to Division 2.

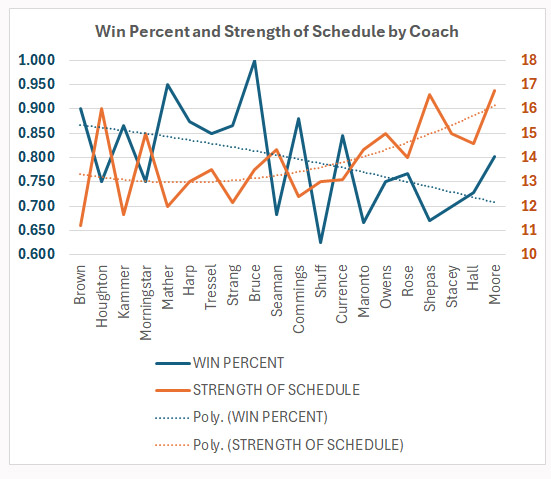

The decreased enrollment, coupled with having fewer senior players on the roster, has certainly had had an effect on Massillon’s winning percentage. During the 1950s and 1960s, prior to the enrollment drop, the winning percentage was .866. Subsequent to that time and up until the present, the winning percentage has fallen to .732. Fortunately, it has been a very fine .895 during the last six years of Moore’s tenure, even with the large parochial schools now returning to the schedule.

Percent of Students Playing Football

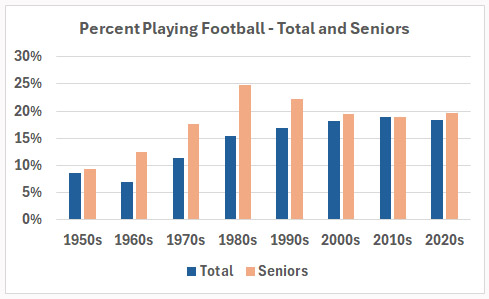

Across the country the number of high school boys playing football has declined, by as much as 3% per year, according to several national publications. The most mentioned reason for this is the potential for concussion due to the physical nature of the sport. In addition, during these days of instant gratification among teenagers, if a starting position on the team isn’t available, then the interest in participating is lacking. Conversely, the media also notes that lower-income students are more prone to participate, in spite of the safety concerns.

In Massillon the participation rate among all boys in the top three grades has constantly increased over time until the 2000s, when it steadied itself at around 18%. The senior class rate is also around 18% at this time, but it did see a surge up to 25% in the 1980s before settling back.

For many years Massillon students embraced the privilege of wearing the orange and black, in spite of whether or not they possessed athletic talent. However, today that seems to have changed, as

the vast majority of seniors on the team tend to contribute when the game is on the line. So, some of what the media proclaims may be also be true for Massillon, but the Tigers have still managed to maintain a high level of participation. For comparison, the rates for several local schools are much lower, as shown below in the Federal League:

- Lake – 20%

- North Canton – 14%

- Green – 12%

- Jackson – 11%

- Perry – 11%

- Canton GlenOak – 9%

- Canton McKinley – 6%

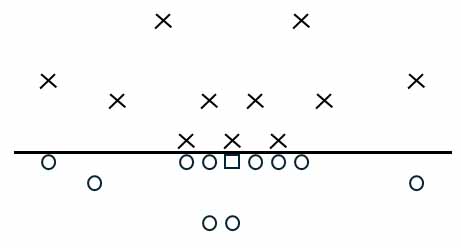

Physical Stature of Players

Finally, a mention should be made of the changes in the physical sizes of the players. Fifty years ago, a high school offensive line would average around 185-200 lbs. But today, with the pass blocking demands of the spread offense, the average has ballooned to around 250 lbs. or more. Would this have discouraged the smaller student from participating? Perhaps. But the Tigers have a top-of-the-line strength and conditioning program coupled with enhanced nutrition guidance that allows players to gain the needed strength and weight that is now necessary to get onto the field.

But it goes even beyond that. Here is how Massillon Strength and Conditioning Coach Dan Studer describes his program:

“Nutrient supplementation is relatively new and has seen some pretty significant advances over the past 30 years. Athletes can supplement a large variety of macronutrients, vitamins, and minerals that are necessary for building muscle and enhance recovery from training. In addition to that, sports science advances have taught us how much and when to take supplementation before, during, and after workouts to stimulate specific adaptations to training. It’s easier for us to pack on size and muscle.

“Training looks completely different than it did 10 years ago, let alone 20, 30, or 40 years ago. Strength training is still relatively new to all of athletics when we look at the big picture. In the early 90s strength coaches were mostly non-existent at the high school level and even at most colleges. When I played division 2 college from 2000-2005 our strength coach was just a D-line coach who had played some professional football; he knew very little about strength training at all. They didn’t even have a paid position for a strength coach. If you were lucky enough to have a strength coach who ran a program, they were very basic and not based on sound principles or practices. Today almost every high school has some form of a weight room and top tier programs have dedicated strength and conditioning specialists with a Master’s Degrees and national certification.

“How we train has come a long way as well. Most of the exercises we do today were not even invented 20 years ago. We have a much better understanding of how to develop muscle by manipulating the reps, weight, and rest in every workout that we do. With technological advances in just the last 4 or 5 years we can now easily customize workouts to fit the needs of individual athletes to optimize training for size, strength, power, and speed. We have a really good idea about what to do, when to do it, how hard to do it, and also when to do nothing at all. We monitor volume, intensity, rest, and effort to optimize training and enhance recovery to build the best athletes possible.”

The Massillon physical training program has certainly helped maintain a healthy participation rate of 18% over the past thirty years.

Conclusion

Massillon enjoyed a high level of football performance for a number of years, which was supported by a sound level of participation as reflected by the sizes of the rosters, only to see it suffer when the school’s enrollment began to decrease. Fortunately, the program has steadied itself over the past thirty years in terms of school enrollment and roster size, unlike what other schools around the area and the nation are experiencing. Plus, to the delight of the avid Tiger fan base, the previous performance level has begun to return. And the strength and conditioning program is certainly a large part of that.

“That was my senior year,” Wells recalled much later in life in a letter to Charles Gumpp, President of the Massillon Football Booster Club. “I was a ‘new boy’, having just moved to Massillon that summer from the wide open spaces of South Dakota, Wyoming and Nebraska. The first day at school several of my classmates came around to suggest that of course I was coming out for football. And although I protested that I had never had a ball in my hands, they countered with the argument that I was a good-sized lump of a boy and would make a fine prospect. So, I promised.

“That was my senior year,” Wells recalled much later in life in a letter to Charles Gumpp, President of the Massillon Football Booster Club. “I was a ‘new boy’, having just moved to Massillon that summer from the wide open spaces of South Dakota, Wyoming and Nebraska. The first day at school several of my classmates came around to suggest that of course I was coming out for football. And although I protested that I had never had a ball in my hands, they countered with the argument that I was a good-sized lump of a boy and would make a fine prospect. So, I promised. A few years later he enrolled at the University of Michigan, where joined the football team as a tackle, with his 1909 team posting posting a record of 6-1. The following season the Wolverines finished 3-0-3, defeating Minnesota 6-0 to win the Western Conference championship. Wells was stellar. playing the first three games at right tackle and then moving to right end for the remainder of the season. For his effort he was named 1st Team All-American by Walter Camp.

A few years later he enrolled at the University of Michigan, where joined the football team as a tackle, with his 1909 team posting posting a record of 6-1. The following season the Wolverines finished 3-0-3, defeating Minnesota 6-0 to win the Western Conference championship. Wells was stellar. playing the first three games at right tackle and then moving to right end for the remainder of the season. For his effort he was named 1st Team All-American by Walter Camp.

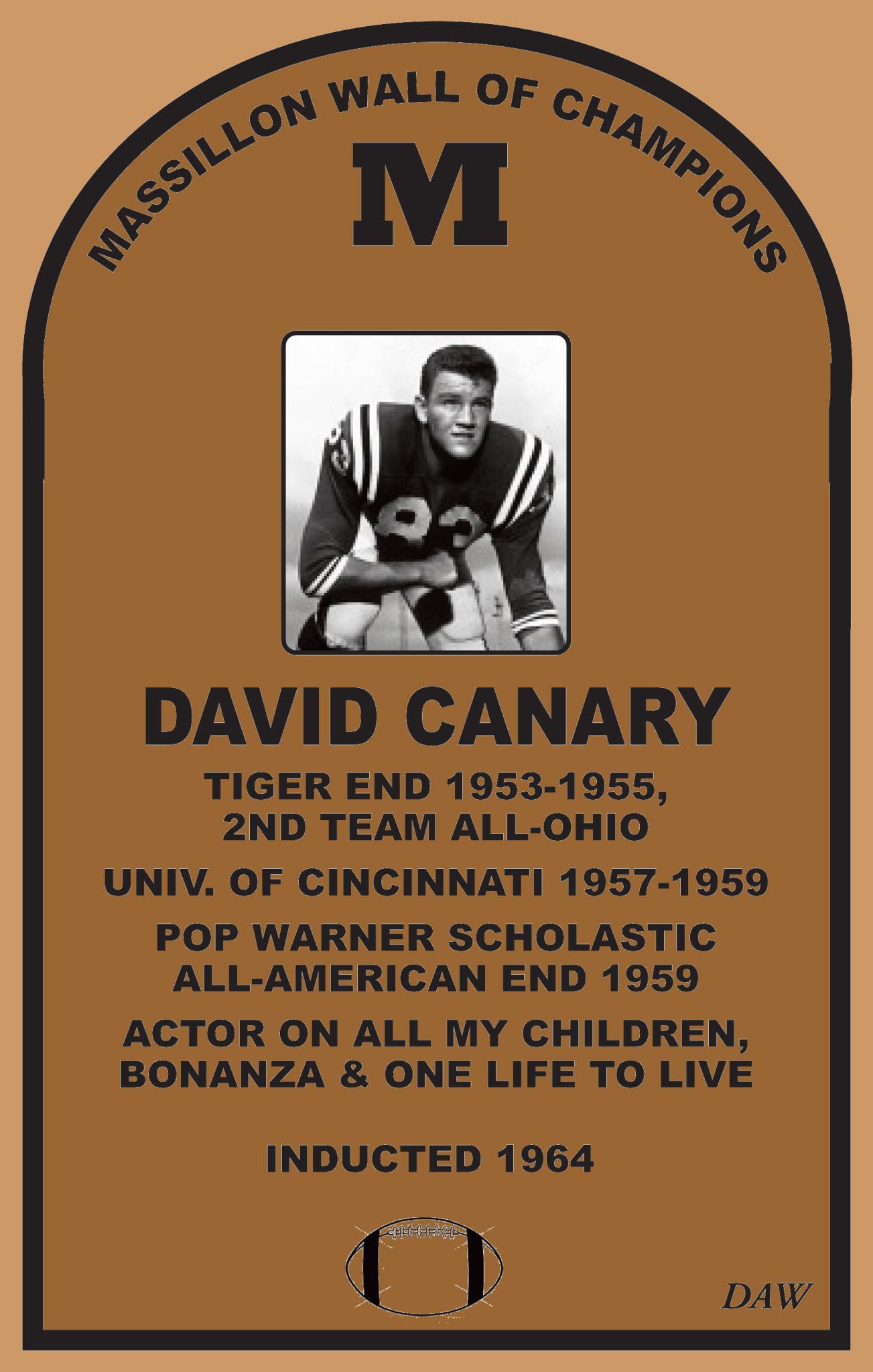

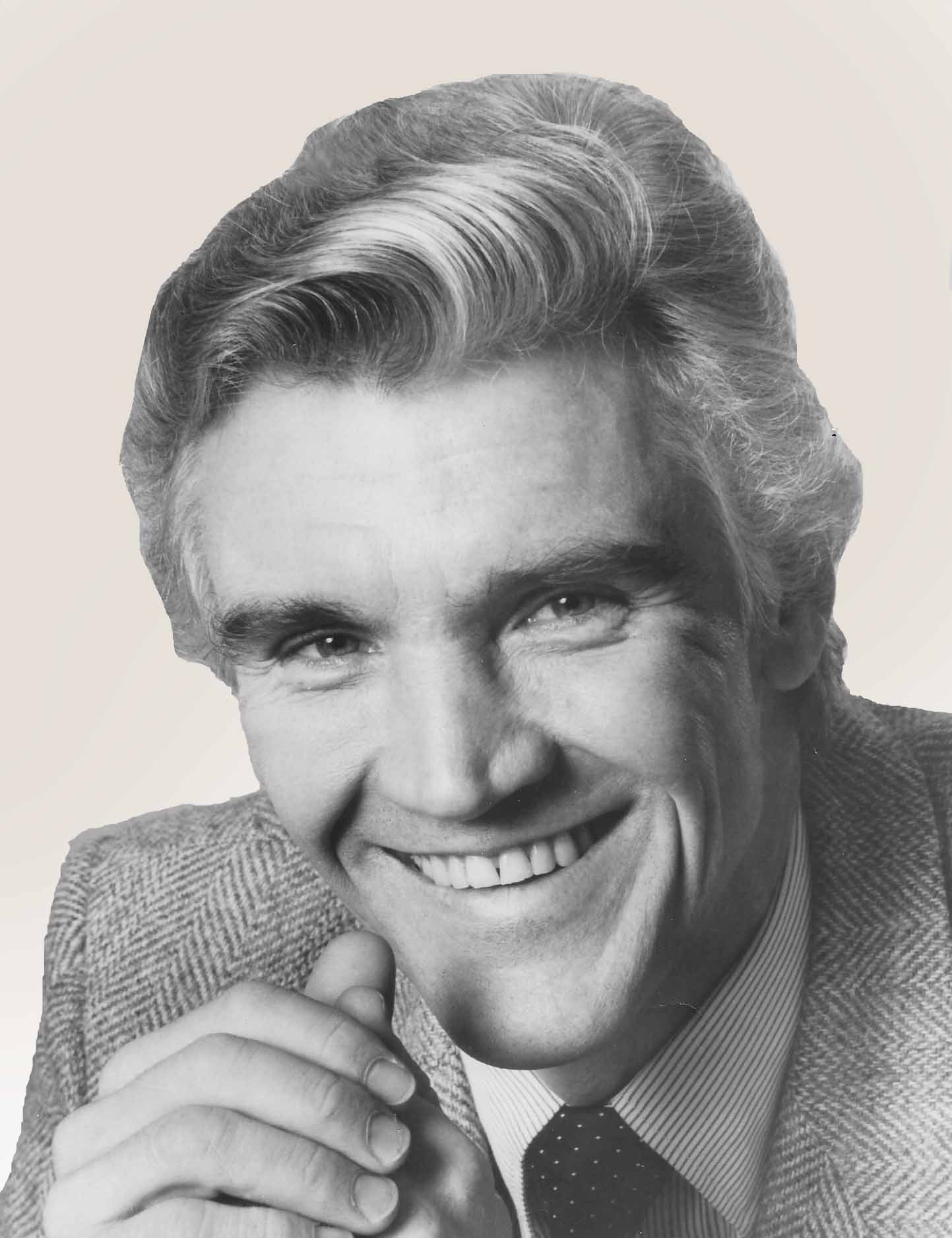

David was an acclaimed and accomplished actor, starring on TV, in dinner theater, and on and off Broadway. But he first starred as an acclaimed Massillon Tiger. Born in Elwood, Indiana, he moved to Massillon at age five and grew up there. As a Tiger, he played both ways, at offensive and defensive end, and was awarded 2nd Team All-Ohio honors following his senior year, in 1955, on a team that finished second on the state. He attributed his success to his work ethic, which he learned while traversing through the city’s various schools. He always gave 120 percent every time the ball was snapped. He said he wasn’t very fast or big. But he was a good student of the game because he had to be. He just did what the coaches said and learned the fundamentals and tried as hard as possible on every play. He said, “I owe a lot to football!” He also played baseball for the Tigers. High school friends called him “A nice guy, a humble guy.”

David was an acclaimed and accomplished actor, starring on TV, in dinner theater, and on and off Broadway. But he first starred as an acclaimed Massillon Tiger. Born in Elwood, Indiana, he moved to Massillon at age five and grew up there. As a Tiger, he played both ways, at offensive and defensive end, and was awarded 2nd Team All-Ohio honors following his senior year, in 1955, on a team that finished second on the state. He attributed his success to his work ethic, which he learned while traversing through the city’s various schools. He always gave 120 percent every time the ball was snapped. He said he wasn’t very fast or big. But he was a good student of the game because he had to be. He just did what the coaches said and learned the fundamentals and tried as hard as possible on every play. He said, “I owe a lot to football!” He also played baseball for the Tigers. High school friends called him “A nice guy, a humble guy.” After graduating, David continued his athletic career at The University of Cincinnati on a football scholarship. There, he continued to play both ways. In spite of having a small stature for a lineman (5’-11”, 172 lbs.) he was good enough to be named All-Conference. He was also a fine student and was recognized as a Pop Warner Academic All-American. At the end of this time at Cincinnati, Canary graduated with a degree in Voice, and was then selected in the second round of the American Football League draft by Denver. Only, tired of football, he instead joined the Army, where he was also a member of the theater group. He even won an All-Army entertainment contest.

After graduating, David continued his athletic career at The University of Cincinnati on a football scholarship. There, he continued to play both ways. In spite of having a small stature for a lineman (5’-11”, 172 lbs.) he was good enough to be named All-Conference. He was also a fine student and was recognized as a Pop Warner Academic All-American. At the end of this time at Cincinnati, Canary graduated with a degree in Voice, and was then selected in the second round of the American Football League draft by Denver. Only, tired of football, he instead joined the Army, where he was also a member of the theater group. He even won an All-Army entertainment contest.